|

(AND HOW TO SURVIVE SUBMITTABLE.COM) Author Kurt Vonnegut once said, “When I write, I feel like an armless, legless man with a crayon in his mouth.” I know the feeling. Each new story I write, I consider, “How did I do it before?” I did it without knowing what I was really doing, with odds not in my favor.

Vonnegut also said that writers “have to be jumping off cliffs continually and developing wings on the way down.” My favorite stories of mine surprised me along the way. If you’re being surprised, you may be doing something right. Publishing your efforts is no less harrowing. When I began getting my short stories published in print journals just before the start of this century, I supported the post office. In those days, you printed out your story on perhaps the best rag-content paper you could find, created a cover letter, and sent it all off to a magazine or publisher with a self-addressed stamped envelope (SASE) for its return. The challenge is that editors don’t know you, there’s so little space, and the submissions come by the hundreds if not thousands. I once agreed to be the judge for a Writer’s Digest play contest. (I started as a playwright.) I was sent over 620 plays. If I knew by page two it wasn’t a winner, I’d move on. When I submitted stories back then, each story cost about $2 in postage each way i.e. $4 a story. I received hundreds of rejections. Still, I was looking for the editor who loved my subtle humor. I ended up getting over two dozen stories published this way. You just have to endure the many rejections. Rejections often came on a three-inch-by-five-inch piece of paper that said, “Thank you for thinking of us. Unfortunately, your piece does not fit our needs at this time.” It would be signed, “The Editors.” At this time? I’d then spend more money on postage to other places. I’d keep track of the rejections on a spreadsheet. I didn’t think about the postage costs. Now things are different. Almost all literary journals, magazines, and publishers want you to send your stories digitally, most using Submitable.com. It might be called Rejectable.com for the efficiency at being rejected. A few of my friends who’d been published often earlier in their lives are deeply frustrated with Submittable.com. They never get published this way. I decided to try it for myself with my new batch of short stories. Even though I’ve been published in a number of top-notch journals over the years, I realized that while all of my friends loved hearing I was published, few if any would buy the journal I was in. Rosebud was available in almost any Barnes and Noble store, but others, such as the Clackmas Literary Review, a consistently beautiful book, could only be bought from the college itself. This time, I got to thinking, “With this being the new age, why not get published in an online journal?” At least friends might read it once you gave them the link. Thus, I started my new journey. Submissions often have a reading fee to support the cost of Submittable. I decided right away if the fee was over $5, the cost in postage, I wouldn’t submit. Some journals seem to exist only for making money this way. Beware of contests that ask $15 or more dollars. I came across one that wanted $40. On Submittable, you’re allowed to write a cover letter. Do that. It’s your best chance for editors to get intrigued by your piece. Don’t give spoilers. Make the editors curious. All said, you’re likely to be rejected. As writers, we’re in the rejection business. If you get rejected, and there’s a name of the rejector, write that person a thank you. You can do so by clicking “reply” on the rejection. The point is to get them to remember you positively for the next time you submit. Editors almost never get thank-you’s. Rather, when I was an editor, I was told how stupid I was in rejecting them and that their cousin told them it was good and would make them famous. “You lost your chance,” they would say, accompanied by an expletive. Yes, that was the way to win me over. Those of us in the office would put the most outrageous letters on the company refrigerator. My goal in sending out these short stories was not to end up on any company refrigerator. If any of my stories received six or more rejections, I'd relook at it to see if the first page was grabbing enough. Would a reader understand the goal of the protagonist? Does the ending satisfy? Often, I'd find things and tweak my story, then send it to new places. Another approach to finding the right place is to simply look up online the journals you know of or have heard about. One of my former USC students, John Fox, created a list, constantly updated, of the best short story publishers, which you can see at his Ranking of the Top 100 Best Literary Magazines. Some of them require you to mail your story the old-fashioned way. Keep track of your rejections, if after two or three rejections by “the editors,” cross them off your list. They aren’t personal. Go for places that look more promising or the editors give you their names. There are always more places. Keep a spreadsheet of your submissions. When you get accepted, highlight the publication on your spreadsheet. I’m happy to say after over a hundred rejections, I started getting acceptances. Most recently, “The Aviator, Eastward” appeared in Barbar Literary Magazine, the same place my first story was published in this batch. The short story follows a young woman, Callie, still living at home in Los Angeles, meeting her secret boyfriend, Harley, at a graveyard. He has news for her. You can read it here: https://www.bebarbar.com/blog/the-aviator-eastward For my first story online, “Views from an Italian Bridge,” click here: https://www.bebarbar.com/blog/views-from-an-italian-bridge Barbar has also accepted a third story, "East-Egg Dancing. Click here: https://bebarbar.com/2023/08/21/east-egg-dancing/ My story “Dietmar and His Very Bad Week,” will be published in the next issue of Rosebud later this year, Issue #71. Get it at Barnes and Noble or online. This is all pushing toward my goal of getting all the stories published first in journals and then as a book. By the way, you are not likely to get rich in getting short fiction published. At best, you might get $15 per story but more likely nothing. A book might bring several hundred dollars in advance. You write and publish this way because you’re compelled to. As Vonnegut also said, “Talent is extremely common. What is rare is the willingness to endure the life of the writer.”

1 Comment

HOW TO DETERMINE WHAT YOUR NEXT PROJECT WILL BE

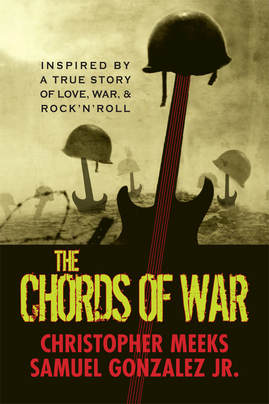

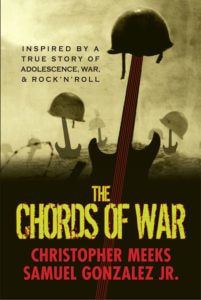

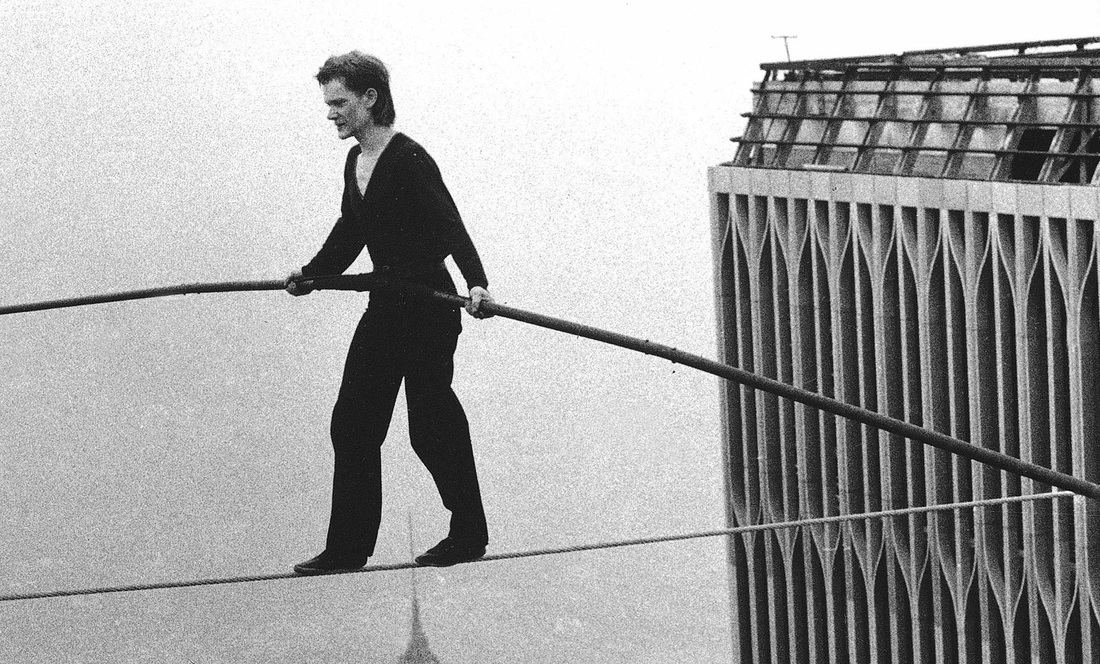

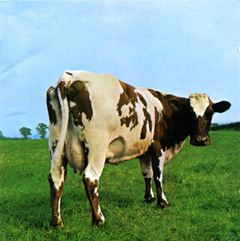

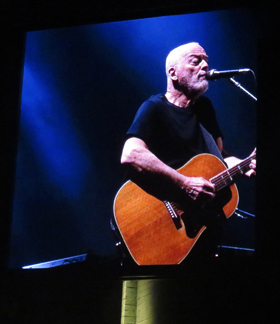

A blogger asked me how I came up with my next book. I'd never thought about the process before. I was momentarily stumped. I told her I'd get back to her. How did I come up with ideas in the past? Determining a project has never been a deeply conscious effort. I often start as I’m doing here, with a topic, a vague idea, and I just start typing. For example, a play I wrote that’s never been produced takes place on a New York City garbage barge that goes to the South to dump its load. When people protest in the Southern port town, another Southern city has agreed to take it. The small crew fights among each other what to do next. The barge hits the high seas again, only to be turned away. They keep getting turned away throughout the Caribbean. After picking up people from a sinking ship, The barge becomes lost in the Bermuda Triangle. It’s funny in a Samuel-Beckett-like way. The production costs, I figured, are minimal. You just need a stage and garbage. I bring this up because not every idea is necessarily commercial. I follow my curiosity and instincts. What many people don’t understand is that writing is thinking. I didn’t know if writing this play would interest me at first, so I simply wrote some. It became so interesting that I ended up taking a UCLA class in existentialism after a few drafts. Beckett wrote after World War II, when existentialism was big. My play would have to be considered post-existential. I took this class to really understand what I was writing. I was obsessed. It occurs to me that obsession is a good thing for a writer to have. After all, any writing project will take months if not years. You better be curious and unstoppable. So, how did I get the topic of a garbage barge in the first place, and how did I choose to even try writing about it? I’d heard a news story about a real garbage barge being turned away. I had an odd thought: how weird would it be to captain a barge of garbage that no one accepts? Who wants garbage in the first place? Then, as if the universe was directing me, I heard a song on an alternative radio station. The song had a chorus, “I’m a garbage barge captain, and I have nowhere to go.” Ah! Let me pursue that. My protagonist would be a garbage barge captain lost on the seas as we are all lost in our world. Aren’t people feeling particularly lost now that they have to stay at home? Maybe I was ahead of my time. I use that play to illustrate that a) what playwrights and fiction writers do is weird, b) almost any job is weird when you think of it; how would you like to be Anthony Fauci working for a president who suggests an intravenous shot of detergent? And c) follow your bliss. Your curiosity may take you places. Another example is in my most recent short story collection, The Benefits of Breathing. I needed at least one more story. What should I write about? Nothing sprang to mind because my 91-year-old father had just put himself in hospice care at home, even though he had nothing killing him per se. However, old age had taken away his concentration to read; he didn’t have the stamina anymore for golf; his hearing was declining. Like the Indian chief in the old film Little Big Man, my dad decided it was his day to die. However, it took him nine months. Before he passed, though, his state of mind captured me. If he was awake, he was happy to talk, intrigued by his decline. “I stood up today, and my legs just gave out. I hit my head on the floor,” he told me on the phone. Rather than run from his state, he talked about it. Rather than not think about it, I wrote a story imagining his death. My father was sleeping about twenty-two hours a day then, and he told me he was dreaming not of important people in his life, but of people he barely knew, people from way back, such as a client he had golfed with or an old elementary school teacher he didn’t particularly like. That’s where my story started. I wasn’t sure it would become a full story. In the end, it’s the title story, The Benefits of Breathing. What might my next project be? I don’t know. I’m waiting for something to strike a chord. I mentioned the coronavirus here, but soon such stories will appear by the boxcar load by people battling boredom while feeling frightened. Maybe I could approach the topic in a metaphorical way. All I know is my next project will be a) fictional and b) it’ll be about something. My best suggestion is write what doesn't bore you. If it starts get boring, then have the characters do something that makes you laugh or jump. Be interesting to yourself, and you'll likely be interesting to others.  Many weeks ago, before my war novel, The Chords of War, was published, I was interviewed by blogger Justin Oldham, and so was my co-author, Sam Gonzalez. Mr. Oldham asked good questions, and then I forgot about the interview. Recently, his blog came out that gives deep insight into the novel, America's wars, and novel writing. Here is his piece with a link to his site: The Chords of War By Justin Oldham The Chords of War by Christopher Meeks and Samuel Gonzalez, Jr., is a story of 21st Century self-discovery that takes the reader through the pain of personal growth, into the horrors of war, before it arrives at wisdom. This fast read has a basis in reality that is sincere enough to make you think. Ideal for anyone who doesn’t quite know who they really are just yet or what they want to do in the future. Portions are reminiscent of post-Vietnam fiction. I submitted questions for the author and his source of inspiration. Samuel Gonzalez Jr. is a filmmaker and songwriter. The character of Max Rivera is the name of his fictional counterpart, who stands in for him throughout the novel. Max experiences the tragedy of September 11th (2001) at nearly the same time he's kicked out of the rock band he wanted so much to be a part of. What you read in these pages is more than a search for identity; it's a literary portrait of millennial uncertainty. Like so many young men before him, Max chooses to enlist in the U.S. Army for a dose of discipline. The estrangement from his friends and sudden derailment of his musical aspirations after many loud and hurtful arguments is presented as flashbacks, while the story moves forward through fog of war as it is now perceived by today's youth. For anyone who can remember the 1970s, this story strikes a familiar "chord" because it reads like the recollections of a Vietnam veteran. Vietnam-era fiction emphasized just as many patriotic themes as are represented here. Readers are given a sense of the uncertainty that was so common for millennials immediately after the gruesome televised destruction of the World Trade Center. Anyone born after 1980 has a hard time comprehending the scope and scale of the Cold War (1947-1991). The Chords of War is a testament to the shock and surprise felt by the millennial generation, much like our grandparents endured when Imperial Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. What begins with rejection by people Max thought of as friends later becomes a departure from people and places he didn’t really fit into. As much as Max loves his country, he has a hard time finding his place in it. Being an MP (military policeman) during the Iraq War feels like Vietnam-era fiction because chapters present flashbacks to what led Max to join the Army. Music plays its own part in the unfolding story. It’s a personal refuge for Max that also serves to inspire him while he adapts to structured military life in a chaotic war zone. His discovery of Vietnam-themed films like Apocalypse Now and Full Metal Jacket underscores the fact that he, and the author who created him, are all too are of the similarities. I asked Christopher Meeks: Do you share Max Rivera’s taste in music or literature? His reply explains why you’re now able to read this story. “This question makes me smile because in writing the book, I had to imagine I was Max who was mostly Sam. While I love music and knew some of the music Sam did in 2005-2007, I also came to see that Sam as a musician loved and even played some of the classic rock I grew up with. Thus, some of the older music is what I loved, too. Sam suggested many of the bands in this book, and then I’d go into Amazon and YouTube and listen to these bands until I found songs I really liked, and then I’d run them past Sam. What he liked of my choices went in. At other times, Sam simply said exactly what they played at a certain time in their Humvee." Ever since consumers could walk about with a music player of some kind, we have thought of life in terms of music. Anyone who likes the history of music will appreciate how references to specific tunes provide flavor to the chapters they occur in. Meeks explained why music mattered. “Sam is a filmmaker. Like me, he builds stories in scenes. I sensed he was always thinking of the soundtrack to this book if it were a movie.” The pointlessness of modern war has been in the minds of writers and movie makers since the Korean War. The Chords of War does more than portray what are now all-too-common consequences of failed foreign policy. The first-person perspective allows a reader to understand why Max eventually returns to songwriting and occasionally performing for the enjoyment of his comrades. It’s part of that discipline and purpose he looks for. To read the rest of Oldham's fabulous piece, please click here. A piece I wrote about Vietnam and Iraq can be read on another website. Click here for that piece.  The Chords of War, a contemporary war novel that I wrote with my former student, Sam Gonzalez, has just been published. Sam had fought in Iraq during the surge, and this is a fictionalized version of what happened to him. It's a tale of punk rock teenager Max Rivera from Florida, who seeks purpose as he tries to understand why his life always teeters between music and mayhem. After he's kicked out of his band on tour, he joins the Army to change his life. It's after 9/11, and he finds himself under fire in Iraq, part of the surge in Baquabah. In order to deal with his teen angst and raging hormones among daily patrols, coordinated battles, and women fighting alongside him, Max creates a new band with soldiers. Will Max and his friends make it? We've received incredible responses to the book, as you can see on Amazon. Two professional reviewers have also weighed in so far: “Strong writing, acrid veracity of language and emotion, this little book is an important one – one we all need to read for ever so many reasons because the content affects us all, now and always. Highly recommended." -- Grady Harp, San Francisco Review of Books “The Chords of War” may be destined to have the impact of “All Quiet on the Western Front” as the defining novel of the Millennials’ war in Iraq. It has already made my 2017 Top Three list of books." -- Linda Hitchcock, Midwest Book Review Below, blogger Teddy Rose interviewed us. INTERVIEW: TR: Please tell us something about the book that is not in the summary. (About the book, a character you particularly enjoyed writing, or anything else.) CM: A book like this is a distillation of much more. Originally, it was going to be a linear tale that starts in book camp and goes to the war. As Sam told me his life before the war--in high school, in bands, and in love with various girls--I realized we had two vivid story lines: before the Army and then after joining. Also, Sam didn't mention it right away, but women were in his platoon. Women could join the military police, and MPs were used in Iraq on the front lines. Women were fighting on the front. Women were often gunners in the Humvees. Suddenly I could see this was a larger story than just a guy joining the Army and starting a band over there. This would be a story of a kid coming to understand many things:. in particular, the Army, war, relationships, and music. SG: For years I knew there was a story here just waiting to be discovered. It wasn’t until my collaboration with Chris where we went behind the curtain of what started as a rock band prepping for a different kind of war in Iraq to a tale of young soldiers struggling to remain sane, forming intimate relationships, controlling their fuelling desires for more and growing up, all of this being seen through the eyes of young men and women. War is a heavy burden on any person, but particularly with this generation – a generation who although move much faster than the Vietnam era boy and girls, also seemed to mature slower and have a different outlook on life all together. It was interesting to show people what war is like, not in a way we have seen before, with heroes running through bullets or men charging through open plains. This was a war fought by kids who had no idea what was even going on, like children in a sandbox. Those are the images of the chords of war – the chords of truth. TR: Please tell us about your collaboration from start to finish? CM: I've written by myself for years, although at one point, I'd worked with two different people on screenplays. Working with Sam was unique as I had my protagonist in front of me, and I could ask him anything I wanted--and he'd tell me. I had not been to Iraq. This was his life. I have read many war novels, including those by Ernest Hemingway and Tim O'Brien, but I already knew from Sam's stories this was a different war. Sam would read over what I wrote. Often what I wrote would bring up memories of another situation, and he'd tell me something new. I wrote detailed notes about everything. Sam is incredibly gifted as a film director, and he has a rich understanding of story structure. Thus, he offered many great ideas. We basically never told each other we hated anything. Rather, if something didn't work for one of us, we'd offer suggestions for a change. Because this isn't a memoir but a novel, our idea was to aim for the truth of what it felt like for Sam, even if that meant creating or exaggerating something. How if felt was most important. After the third draft of the book, after I'd made a dummy version of the book bound by covers, Sam read the whole thing thoroughly, and we went through the book page by page. If there was a sentence, paragraph, or section that didn't feel right to him, he'd read it aloud and consider what was off. We'd work out what needed to be done. Sometimes I gave a reason why I thought it should stay, but most of the time, he spoke so well, it made sense to alter it. Sometimes it was just a single word. Sam is meticulous--and yet he's so respectful and considerate, working with him was a joy. In the end, we had a book we both loved. SG: I always love the energy and passionate creativity that comes from a strong collaboration. To me, that is the root and spirit of any great project. Sometimes that root grows into something beautiful that lives on for others to enjoy, and sometimes it withers and falls apart before it even has a chance to see the light of day. I had taken a class at the Art Center College of Design in children’s literature, where Chris was my professor, and he always encouraged and pushed me to delve deeper into my storytelling – always with respect and a genuine care for characters. When I was searching for a collaborator to help me take “The Chords of War” to the literary world, there was no doubt in my mind that Chris was the right choice. The minute we sat down for our first meeting to discuss, I knew deeply that this was going to evolve into something special. It was the beginning of a three-year road, and upon shaking hands, we not only invested in the story but in our upcoming journey ahead together – like two guys going out to sea with only the clothes on their backs, a paddle, some memories, and a typewriter. On that boat, Chris would listen to my experiences, carefully notating everything in great detail and expanding on those by asking very in-depth questions that often cracked into my PTSD. Those moments would lead to tears and often unsettling past flashes on thoughts of the past, but Chris was right there and knew exactly how to use that for the best of the book. His sincere love for the story and respect to the detailed moment of my life were carefully handled by him every step of the way. We never fought or came blow to blow with each other, but instead, if we came across a fork In the road, we would listen and find solutions on how to make it better. After many drafts and meticulously reading and re-reading the pages with over a year of additions and improvements, we were finally docked back on shore with more respect for each other than when we sailed off. It was an honor, and I would proudly serve with Chris again – he is a true soldier in my heart – a soldier of literature. TR: Since much of the book came from Sam’s real life experiences, what made you decide to fictionalize the book? CM: There are a number of reasons. Sometimes the way something happened obscures what an experience was like. For instance, say you had a major life-altering experience on a roller coaster at age six, and you had seven cousins with you. Maybe you can explain it better in a story in with fewer people. Another example: I spent my junior year of college in Denmark because I'd fallen in love in Minnesota with a visiting Danish young woman. By the time school started in Denmark, she was living with another man but never told me. I only found out when I landed in Denmark. In retrospect, it was funny, but certainly not at the time. A friend said, "You should write a novel about that." I did--but I didn't want it about a college student in 1975. I wanted it in Denmark now, so I made it about a genius physics professor teaching at the University of Wisconsin who falls in love with a visiting Danish kindergarten teacher. I put my protagonist though hell--much worse than I actually went though--but the deep feelings I had about my time there made it into the novel Love at Absolute Zero. A good novel tells truths. In our novel, Sam and I aimed to tell his truths . He wasn't John Wayne yelling, "Follow me, men!" He was an adolescent experiencing war when he didn't even understand why we were fighting in Iraq beyond maybe it had something to do with 9/11. SG: Fictionalizing the story wasn’t what I initially had in mind. The truth is I didn’t know where to start. Have you ever found a drawer in your home, or an old shoebox full of decades old items and collectibles? When you put all that in there, you didn’t think much of it, but revisiting it was like discovering a treasure trove. There were so many memories bubbling to the surface, so many faces resurfacing after years of not remembering them. Those memories were fading away but, unfortunately, not the pain of those memories. Those never go away. Chris helped me channel that pain and to find the good that helped keep those away. For me it was the music. As we started discussing life details from the beginning of my life until my return home from hell, we both learned together that music was a character in its own right, a true hero that had saved me time and time again – almost an invisible entity that lived through me. That was the magic that spawned the idea of evolving true moments and circumstances and culminating them around fictionalized (although strongly based on) moments that were surrounded by music. This to me was very special. The stories on their own were powerful and true, but once the music element was thrown in, it was like raising the gain on a Marshall stack amplifier and breaking the guitar on stage – the feedback would be endless.I believe this book will be that feedback that lives on. TR: I love the cover, please tell us about it. Did you design it yourself? SG: My friend and graphic designer Jeff Joseph and I did. We had worked together during my Art Center days on large graphic photography. We met one afternoon to discuss possible ideas for the front cover of the book. We wanted something people could relate to, something they had seen before but different. We wanted a new twist that would have them go, “Hey, that’s interesting” or “Wow, I’ve never seen it quite like that before”. When you think of war, you immediately think of the loss that comes with it – the causalities and the innocence lost. The image of the helmet on top of the rifle is the true symbol of that loss and the bravery that once filled that helmet. We knew that would be a great place to start. Now how could we incorporate music into that? We started messing around by placing drum sets, microphones, and more in a war zone – each one looking pretty cool, but once we incorporated the guitar into those helmets in place of the rifle, we stopped and said, “I think we might have something.” We searched endless hours online for great references of the helmet and rifle to get perspective on how to approach it and came across great ideas. We married those ideas and splattered the punk rock style across it with the strings and fonts, and the cover was born. Chris has his book designer (Deborah Daly) who he had worked with for years on his past novels, and she joined in to bring her eye to the image. In the end, it was a true collaboration that together, formed something unique, haunting and full of rock-n-roll. CM: This book came out through a publishing company I had started in 2005, White Whisker Books. I publish four other authors besides myself. After Sam and I finished this book, I felt this book was so big, a bigger publishing company needed to take over. Small presses can go bankrupt, believe it or not, in receiving many great reviews. I had that nearly happen with a book by Shelly Lowenkopf, Love Will Make You Drink and Gamble, Stay Out Late at Night. The short story collection won awards and great reviews. Bookstores ordered. Of course, they went on bookstore shelves, spine out, so few people noticed it, and then the books were returned. Returns are an expensive thing for publishers. That book is still in the red. I couldn’t afford another mass return. So I sent The Chords of War to over a hundred agents. Twenty-five wrote back, and were polite. Six asked for the manuscript. Two later said it wasn’t right for them. Four never got back to me. I decided I loved the control of making the book look just right. I also decided I would not make the book returnable. I have made three versions: hardback, trade paperback, and eBook. This takes me to your question of the cover. I had hired a great book designer, Deborah Daly, who had been the art director once for St. Martin’s Press. Before she even had an idea for the cover, Sam sent me this one. Deborah loved it and added the guitar strings and played with the lettering. She also had a great design for the back and interior. Self-publishers assume the inside is automatic, but no, it takes great care to have the right font, the right size and leading, and make sure each line, paragraph, and page breaks in the right place. It’s the extra attention that helps make a book easily read. I thank Jeff, Sam, and Deborah for being so brilliant. TR: What is your favorite scene in the book? Why? CM: There are so many great scenes, but the most critical for me were the opening and closing of the book, and those scenes changed over time. I happen to love the ending as to me it's lyrical. Iraq isn't about happy endings, and what Sam and what his friends went through wasn't warm and fuzzy -- but Sam and the people in the novel grow, even if there's a sense of ambiguity to some of it. The Iraq War did not end on a sure note, and neither did Sam's experiences. SG: It’s hard to choose a scene because every scene lends itself to another. They all flow together as well as the memories in my head do. The realistic and poetic opening and ending to the novel sure stick with me as pivotal moments during the read, and the relationships between the characters are always my favorite moments – especially when the music is born between them. TR: What are you currently working on? SG: My first feature, Railway Spine, a veteran story of PTSD (this time in the Vietnam War era), has just recently received distribution, so we are preparing for that. I am working on directing another feature film in February 2018, a veteran film with comedic horror elements, which I think will be another fantastic and uniquely different approach to showing audiences the real experiences of a veteran. I’m also teaching my first classes as a professor in film studies in the state of North Carolina, and I’m working tirelessly to get The Chords of War to the next step of getting it to Netflix to be made into a series. When that day comes, it truly will feel like a mission accomplished. I would be honored to work with Chris on that platform and take our collaboration to the small or even big screen. CM: I’d love to work with Sam again. He’s a true talent. Go onto YouTube here and see the film Sam made for my previous novel, A Death in Vegas. Sam even turned me into an actor. I trusted him.He’s a amazing director with a clear vision. Now I'm working on short stories. Alas, I'm going through a divorce but our breakup is amicable -- not about blame but about growth. Maybe I'm sounding like Gweneth Paltrow and her husband Chris Martin of Coldplay, but sometimes relationships end because they've run their course. I didn't want it to end, but that's another matter. It's a confusing time and a clear time. I want to get some of that in some short stories. I've written other stories over the years that have been published about other things, and, like a rock star creating an album, I'm not sure at this point what stories will fit in a unified collection. TR: Which actor/actress would you like to see playing the lead character from your most recent book? SG: That’s hard to say, but it’s definitely been something we have been bouncing around since we are working on bringing this unique true story to the small screen. When that day comes, I would like to cast talented unknown actors for the role so that the story feels authentic and real and nowhere near staged. The music in our veins were true every boot step we took and with every person we encountered – it was unfamiliar and new territory for us. I want audiences to walk that same path, feel what we felt, and experience these actors as if they are people they are learning about for the first time. CM: I trust Sam with that. TR: How long did it take you to write this book from concept to fruition? CM/SG: Three and a half years. Thank you for this interview, Teddy. To see Amazon reviews of the book, click here. To buy the book on Amazon, click here.  As readers and viewers, we want our stories to end in a satisfying yet surprising way. As writers, perhaps too often we make it easy. Yet the best stories have deep conflicts that seem impossible to recover from. Sharp and worthy adversaries get in the way. If you’re the writer, to make your story and ending compelling requires thought and emotion, delaying the inevitable. You need to be willing to structure, to taunt, to tantalize. A case in point is the recently concluded HBO series The Night Of, starring John Tuturro and Jeannie Berlin. Based on Criminal Justice, a 2008–09 British television series, The Night Of was co-written and directed by Steven Zaillian, known for his scripts to such films as The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, Schindler’s List, and Searching for Bobby Fisher. Novelist Richard Price, who also wrote a lot of HBO’s The Wire, joined in the writing.  Because this is a case study, I’ll be giving surprises away. Having published two crime novels, Blood Drama and A Death in Vegas, I admire much in this series and understand what the writers needed to do to pull off this mystery. You don’t have to see the series to follow my points. Rather, see how Zaillian and Price deliver so much. You, too, can offer a lot in your own work. The story revolves around Nasir Khan (Riz Ahmed), a Pakistani-American college student who, when his friends don’t pick him up for a party, borrows his father’s taxicab without permission. At a stop, a young woman, Andrea (Sofia Black D’Elia) pops in his cab, asks to go to a beach, and when they stop, they talk, drink beer, and take drugs. It all leads to a night of sex and more drugs at her classy upper Westside brownstone. When he awakes in the kitchen, he finds her stabbed to death in her bed, and he flees, observed. He’s soon arrested. Things stack against him. In fleeing, he cuts himself and leaves blood. He takes the murder weapon, perhaps thinking he did it. He’s Muslim. His parents are immigrants. They have little money for his defense. Only a few small things stand in Nasir’s favor. He’s likable and seemingly innocent. Also, low-end lawyer John Stone (John Tuturro), visiting a low-end client in jail, sees a vulnerable innocent-looking kid in lockup and decides to defend him. The Dramatic Question Let’s pause here. A critical element in storytelling is to set up the dramatic question. Will Nasir, despite prejudice, the skewed judicial system, and the preponderance of evidence against him, be found innocent and let go? Novice writers often muddy or even avoid the dramatic question. Audiences need to know what to root for on the journey. If an audience isn’t clear who the protagonist is or what he or she needs or wants, the story dies quickly. I’m reading a script now where, after twenty-one pages in, the story skips ahead twelve years and follows someone else. Now I don’t know who the protagonist is or what either the first big character or the second one wants. In The Night Of, the viewer, you, believes in Nasir’s innocence. It’s what you hope for every minute unconsciously. You’re waiting to feel good when he’s found innocent. You’d be happy if that happened at the end of the first hour—but would you? We like surprises and doubts. We like to be taken on a journey, even if it’s dark. Theme Another key element has to do with what is the story about? Why are we spending eight hours on this story or, say, more than seventy hours on Game of Thrones? We never consciously look for a message—and we certainly don’t want to be preached at—but we do seek deeper meanings in our stories. It’s why Christopher Nolan’s films such as his Dark Knight Trilogy, Inception, and Momento stick with us—because they tell us things about our world. Here, Zaillian and Price make the viewer question American society and its fairness. We see that justice isn’t just. Rather, police are overworked and look for easy solutions to close cases. The coroner asks the D.A. how should he make the evidence go her way? Innocent people take plea deals to spend only half their life in prison instead of more . Story guru Robert McKee uses the term “controlling idea.” He says that master storytellers “never explain… They dramatize.” A controlling idea should be expressible in a single sentence, a universal truth. As he writes, “The more beautifully you shape your work around one clear idea, the more meanings audiences will discover in your film.” I never write toward a theme, but at least starting in my second draft, I look for where theme pokes its head out, and I follow its truths. I edit my stories to revolve around its theme, its controlling idea. In the end, your story has to be about something, and The Night Of certainly is. How you get there is most clear in the ending. The Important Ending Over the course of the next seven episodes, The Night Of brings many turns and surprises. As in any good story, your hopes build and get dashed. That’s the job of the storyteller. Nasir awaits trial in Riker’s Island, a dark, brutal penitentiary where his life is threatened. Most of the prison population hates him for being small and Muslim. However, an inmate leader, Freddy (Michael Kenneth Williams), who the prison guards let run his little fiefdom, protects Nasir, bringing Naz into the prison culture. Soon Naz works out in the gym, shaves his head, and gets tattoos. We come to the end, the trial. At this point, Naz looks like a criminal, even if he remains soft-spoken. Stone is not his lead lawyer, but second chair. Rookie lawyer Chandra Kapoor (Amara Karan) runs the defense. She essentially talks Naz out of taking a plea deal. Everything is on the line.  Kapoor decides to let Naz testify, against Stone’s strenuous objections. Stone says a defendant has the cloak of presumed innocence, but if he testifies, he’s assumed guilty and has to prove his innocence. When district attorney Helen Weiss (Jeannie Berlin) cross-examines Naz, we see Naz still isn’t clear what happened. He has his doubts. Weiss’s questions hammer home what appears to be Naz’s guilt. Before this, the viewer has had hopes. We learn that Andrea’s stepfather, the murdered girl’s antagonist, had designs on her estate, worth ten million. He filed for it days after her murder, and the police did not even investigate him. We learn that three other people who met the young couple that night all had criminal backgrounds and motive. The police didn’t investigate them, either. District attorney Weiss plows through these possibilities, brushes them aside. Naz, she says, clearly murdered Andrea brutally, and when he had a chance to call 911 if he didn’t do it, he did not. Weiss appears focused and brilliant—even if at this point she knows of another more likely murderer. When Kapoor has to step aside from delivering her closing arguments in a twist that has to do with judicial ethics, the judge forces John Stone to deliver the final thoughts to the jury. Stone, who has had health problems with eczema, has a major flare-up, has to go to the hospital, and now appears before the jury much like a leper. Can he overcome the D.A’s brilliant presentation and make the jury see? As much as we want that, we have our doubts. Then smart writing and Turturro’s brilliant acting come together. Stone admits he’s not the best lawyer or even used to speaking to juries, not looking the way he does. Still, he focuses on what’s truth and what’s speculation, what’s fair and not fair, and before our eyes, we can see at least some jurers might have doubts about Naz’s guilt. An old-fashioned Hollywood movie might have the jury come back beaming, eagerly saying Naz has been treated unfairly and he’s clearly innocent. Naz and his family would have a big party, and the girl next door (if there was one) would kiss him and everything would be all right. Rather, here, the jury is deadlocked, six to six. That could mean another trial. Still, the D.A., knowing there’s a more-likely murderer, drops the case. Naz is free. It could end there, and we’d be satisfied, but theme now comes most clear. While Naz is free, he’s not the same person. He’s addicted to crack. He’s covered in tattoos. His own mother had felt he was he’s guilty, and Naz knows it. He’s a broken person. Justice isn’t fair. Still, the series makes one more point. Shortly after the murder, Stone sees the murdered girl’s cat now has no one to feed it. He takes the cat home, but he’s deeply allergic to it. Will the cat at least be saved? No, Stone takes it to a shelter. It will have only ten days to be given away or euthanized. Here, Zaillian stumbled on something important. As he said in an interview, “When [Stone], and we, first see the shelter, its stark walls and cages resemble a prison cellblock. This, too, was intentional. And as the cat with no name is carried by a volunteer past the chain-link cages housing loud dogs, it’s an experience not unlike Naz’s when he’s first taken into Rikers by a corrections officer. The outlook for both of them is grim. From there it was a matter of asking, ‘now what,’ ‘what if,’ and ‘then what,’ and ‘then what if.’ This is what writing is.” One of the last images is the cat prancing back at Stone’s apartment. Stone has saved it once again. While justice isn’t always fair, there are the small victories.  To those who follow me: sorry I’ve been away for almost two months. I’ve been literally coughing since that time, and in mid-June, my doctor took a chest X-ray and decided I had pneumonia. The antibiotics didn’t work. I then saw a pulmonologist—a lung specialist. A few CT scans and a biopsy later, my pulmonologist discovered I had a rare condition called vasculitis, an autoimmune issue. During this time, knowing I had a breathing problem—could it be lung cancer?—I read an emotionally powerful book, When Breath Becomes Air by Paul Kalanithi. It’s nonfiction, Kalanithi’s journey through lung cancer. Spoiler alert: he dies. Perhaps I shouldn’t have started the book when I did, but then again, when you’re thinking dark thoughts, you can’t help but consider them. Kalanithi writes so honestly and even lyrically at times, he takes your breath away. For instance, once he’s sat with his initial chest X-ray that proves to him how dire his situation is, he writes, “The tricky part of illness is that, as you go through it, your values are constantly changing. You try to figure out what matters to you, and then you keep figuring it out. It felt like someone had taken away my credit card, and I was having to learn how to budget.” Should he continue on as a neurosurgeon, saving lives, or should he take time off and do other significant things? Before he started chemo, he and his wife focused on whether they could or should start a family. “Will having a newborn distract from the time we have together?" his wife Lucy asks. "Don't you think saying goodbye to your child will make your death more painful?" "Wouldn't it be great if it did?” he says, and adds, “Lucy and I both felt that life wasn't about avoiding suffering.” They go to a fertility specialist, and she is able to get pregnant. They both cheer about it. When he goes through chemo and wonders if it will kill him, he thinks, “I can’t go on. I’ll go on.” I could empathize. When my first doctor said I had pneumonia, as drained and winded as I was, I felt great. At last I had a reason for why I felt so bad. Friends then told me of when they had pneumonia, warning me it was difficult, and still it was better than not having a diagnosis. I finished my antibiotics on the Fourth of July and couldn’t make it to the nearby fireworks as I was coughing too much, too drained to go. I had a sinking feeling I didn’t have pneumonia. Was I headed where Kalanithi went? It took another six weeks for me to get to vasculitis. As someone who had been healthy for decades—a cold being the worst—I found myself thinking differently when I was confined to bed. It opened my eyes, reminding me that people out there, including readers of this blog, have daily physical challenges. Emotional ones, too. At my darkest, I’d consider that maybe things would keep going downhill until it’d be all over. Along the way, two of my lymph nodes became rock hard. I must have lymphoma, I decided. Or maybe I had what the neighbor across the way from us had. He’d gone to the dentist for teeth cleaning, then days later felt lousy. His doctor found the man had sepsis. That affected a heart valve. He needed heart surgery and a bovine heart valve quickly. I realized I’d had my teeth cleaned in early June. You see what happens? When you don’t know what you have, you think of the worst and realize people get bad things. Who says you can’t? The end for most people comes sooner than expected. Philosopher Martin Heidegger felt we should all contemplate our deaths, and once we truly feel it, we can live each day feeling alive and “present in the moment.” Once I did, however, I didn't feel present. I simply felt sad. Look at the things I'll miss. My wife and children. My students. My tomato plants. On the positive side, my energy is back, and I’m writing again. I polished my latest novel, and now I’m deciding on the next book. It’s good to again be the optimist. I also realize, hey, this life isn’t forever. Take advantage of the good days.  Publishing keeps changing, and one needs to listen to the rails (or wire) I became a small publisher, creating White Whisker Books, for one reason: to publish and distribute my short story collection, The Middle-Aged Man and the Sea. My agent didn’t want to send the manuscript out, so a friend from the days when we worked for a small publisher, Prelude Press, said I should start my own business and publish it that way. I did everything we had at Prelude: hire a publicist, send out review copies to big and small reviewers, and create press releases. I had luck on my side. The first review was in the Los Angeles Times, in January 2006, and a few months later Entertainment Weekly mentioned it favorably. EBooks were not a market then, so I sold two thousand print copies mostly through Amazon--incredible for a short story collection. The book has continued to sell steadily, and there are eBook and audiobook versions now. I then published another collection, and found a new agent for my novels, Jim McCarthy at Dystel and Goderich in New York. When he found three editors for my physicist-meets-Danish-lover novel, Love at Absolute Zero, the marketing departments for those publishers declined. They said they a book with science and love would be too difficult. I published the book through White Whisker instead, and it has won awards. Still, the marketing challenges have only become bigger with each book, including for four other authors I now publish. For about a year, I used Bookbub monthly to promote one or two books in our list, and it worked brilliantly, most of the time selling over two thousand eBooks in a day. Of course, big and small publishers learned of Bookbub, and now it’s rare for me to get a promotional space on Bookbub. A marketing plan needs outlets that you can depend on. I’ve had to look for other ways. I’ve tried a variety of promotional sites, including Kindle Nation Daily, but all cost more than they bring in. Of course, traditional advertising says that’s how it works. You advertise in a number of places, and after people see your book seven or more times in different places, they might buy it. Still, such a method hasn’t worked on any of our titles. Things that have worked for short periods are using social media for new books, promoting a new book on a blog tour, and reading in bookstores and libraries for a new book. The common theme “new book” is what counts. Older titles beyond using Bookbub remain a challenge—as does getting onto Bookbub. However, I’m trying something absolutely new. Another friend from Prelude days now works for a major new distributor of eBooks, Hummingbird Digital Media. HDM has created a new approach to selling eBooks, though independent digital storefronts and an app that goes on your tablet or smartphone (Android or iOS systems). Thus, for example, you’ll be able to read on your iPhone or iPad, your Galaxy tablet, your Kindle Fire, your Android smartphone and others. If you have one of these devices, you have to buy nothing more. This is to say anyone can create a storefront and sell ebooks and audiobooks. Those books can then be read (or heard) through a free app called “My Must Reads” on devices people already have. Not only do publishers have their own Hummingbird storefronts, but so do publicists and book bloggers and average people who love reading books. You can bring in extra money through your storefront. Your storefront can be branded with your name or logo. Here’s the White Whisker Books storefront: click here. In order for you to see how the app and system work fully, HDM is letting me give away one of my books, Blood Drama, for free. The directions for getting the book are below. You get to try out the system at no cost or credit card input--for a limited time (the next three days). Description of Blood Drama Blood Drama revolves around graduate student Ian Nash’s bad day. After losing his girlfriend and being dropped from his theatre program at a Southern California university, he stops at a local coffee shop in the lobby of a bank-- just as the bank is being robbed. He’s taken hostage by the robbers. Now he has to save his life. Praise for Blood Drama “Blood Drama is highly entertaining and extremely enjoyable. It is a combination black comedy and crime novel.” - Lori Lutes, She Treads Softly “A murder mystery filled with interesting characters, harrowing encounters and a bit of a love interest between student Ian and detective Aleece make this an interesting and satisfying read.” - Kathleen Kelly, Celtic Lady “Meeks may have daringly stepped into new territory, but he continues to remain in the rarefied atmosphere of fine contemporary authors.” - Grady Harp, Literary Aficionado Directions for the Free Download The following redeem code is good for your download of the book for free from now until June 13 only. You get it from the White Whiskers Books’ storefront. Here are the directions: 1) On your computer, smartphone or tablet use this URL link to the White Whisker Books storefront in your favorite browser: http://whitewhiskerbooks.papertrell.com/id003432116/Blood-Drama 2) Click the “Buy” button, which will open a page where you type your name, email address, and this redeem code: WWBDCM 3) A message will appear congratulating you on your good taste, and an instruction to download the “My Must Reads” app from the app store of your choice (Apple or Google Play). The app will go onto the smartphone or tablet you’ll read with. Use the same email address you used to redeem your free book. 4) After downloading the app to your iOS phone/tablet or Android phone/tablet (or KindleFire or Nook tablets), your book will appear in My Library right there in the app. Read and enjoy. Thank you for enjoying this website. May the book give you hours of pleasure. If you like reading books this way, then you can buy more White Whisker Books and most books from big publishers using the same app. Start your own storefront, too. Note: The photo is of Phillipe Petit walking between the World Trade Center towers in 1974. There are two amazing films about that feat. The first is a documentary, Man and Wire, and the other is a recent feature film, The Walk, starring Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Petit.  A year ago, I wrote a guest blog for Lisa Binion on this topic, and I never reposted it here. Now that I have just finished a new book--ostensibly "literary"--I thought it'd be great to bring this back. You can see the original posting by clicking here. “Literary” is a type of book many people admire, but it’s not a genre that people necessarily seek. It’s even hard to call it a genre the way “mystery,” “romance,” and “paranormal” might be. Books that appear on Amazon’s literary bestseller list, for example, reveal how widely defined “literary” really is. For instance, the week as I write this, number one is Catherine Ryan Hyde’s novel, Where We Belong, about a fourteen-year-old girl whose younger sister with a type of autism falls for the neighbor’s Great Dane and gets better. Then the grumpy, awkward dog owner moves away. To help her sister, the fourteen year-old must find this man. This story could easily be called Young Adult. Also on the list is Helen Bryan’s War Brides, about five women in England who are evacuated from London in World War II and become friends to deal with their many struggles. This might be called Historical Fiction or Women’s Lit. Add to this Nicholas Sparks’ The Best of Me. He’s known for his epic romance novels, such as The Notebook and A Walk to Remember, which start in high school. This novel is similar and could easily fit into Romance. These join the list with Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Goldfinch, which most people would unabashedly call literary. Still, in my mind, what all the novels here share is good writing, and they’re stories about interesting, even ordinary people. I wrote my two collections of short stories and my first two novels without any thought of genre or being “literary.” All my stories simply revolve around some huge problem that comes to an otherwise ordinary person. I put pressure on my characters and then look to see what they do. As one of my mentors, playwright Robert E. Lee, co-writer of Inherit the Wind, said “plot is nothing more than following what interesting people do.” When it came time to market my first books, they were marketed as “literary.” However, my last two novels are crime books. I fully understood I was writing in a genre. I didn’t study the genre to be a copycat and fit some steely paradigm. A mystery novel, at its core, has to have a murder and a mystery about who did it. There have to be dead ends. Still, that didn’t stop me from making my protagonist, Patton Burch, an interesting man. Patton runs a beneficial bug business for organic gardeners, and when the gorgeous and smart model he hired to be a ladybug for his booth at a Las Vegas convention turns up dead in his hotel room, and the police focus on him, he breaks off to solve the mystery and clear his name. I knew going in that I had to have surprises, but there’s something about the way I see the world—it’s absurdity—that still slips in. If writing rich characters and coming up with certain truths about life is literary, then that’s what I’m still doing, but within the mystery genre. I have to say, when I was in the MFA writing program at USC—and then later I taught there—we never focused on “literary” or any genre, for that matter. We just focused on writing stories. Of course, in hindsight, I think it could be helpful to aspiring writers to understand genre and what they’re writing so if they’re aiming for certain readers, you can meet their expectations while meeting your own. If you’re as an eclectic reader as I am, then you’ll have similar tastes in what you think of as a good novel. Off the top of my head, I’ve loved A Visit from the Goon Squad, the non-linear Pulitzer Prize winning story of a group of intersecting characters, including a record producer. I thoroughly enjoyed and am about to teach in my English class The Yellow Birdsby Kevin Powers, which takes place in Iraq and is a different story than the one I’m writing. I also love rereading The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler, a detective novel, which my wife is reading now. All can be considered literary. Shelly Lowenkopf, in his fabulous The Fiction Writer’s Handbook, offers an understanding of hundreds of terms that writers use. He defines “literary story” as “a prose narrative written to discover a feeling, intent, or meaning. There is an exercise of the writer’s curiosity to see where the problem will lead and whence the solution—if any—will come. There is also a prose narrative in which the writer knows the conclusion or believes the provisional conclusion is, in fact, the conclusion, then retraces in order to clarify the obstacle.” I can guarantee few if any writers start out writing a novel saying, “Let me figure out an ending and then I’ll retrace it to clarify the obstacle.” Such a definition is more of what an agent, publisher, or critic might think in trying to analyze a story. In fact, Lowenkopf dives into what a writer often does, which is begin the literary story “with a dramatic construct located beyond his ability to see an easy way out.” A literary story, he says, “is a contract made by the writer not to write anything safe.” I love that point because with anything I ever write, even if I create a detailed outline (and I do so for novels), I’m never sure if my story will work. Will it meet my initial hopes for it? I write many drafts until it works. Surprises happen as I write, so that I have to dive back into my outline and change things. My outlines have their own lives. They are not etched with a chisel in granite. I know some book reviewers in the future might try to figure out the path I’ve taken to what I write and publish. For instance, the novel I’m now writing is a first-person war novel that takes place in Iraq in 2006, and how does that fit in with my other novels? I’ll let readers figure it out. My novels include a protagonist who is a film producer, another who’s a major quantum physicist, one who is a graduate student writing a dissertation on playwright David Mamet, and now in A Death in Vegas, my beneficial bug guy. All I can say is to jump in and hold on for an experience. If that’s literary, that’s what I do. Amazon Link: A Death in Vegas Lisa Binion's review of A Death in Vegas, click here  I’ve been going to rock concerts more steadily over the last few years. It’s something I did in high school, yet now that I’m older, I ask myself why now? It’s a rediscovery of the mystery of music. I’m not clear how great music works, or how people make it, yet I sense it’s similar to why I write fiction. For me, writing does several things. By slamming different characters and situations together, I witness people struggle, trying to attain whatever their goals are, much as I am. Sometimes, like me, they are also trying to understand things. Yet there’s also the mystery I love in writing. I’m never sure if a story will work out—and sometimes it doesn’t—but I’m curious to see what will grow. As author Rick Moody wrote after his novel The Ice Storm, “Sometimes I think words are so beautiful so flexible so strange so lovely that they make me want to weep, for the import, for their proximity to eternal mysteries.” Maybe it’s also why I cultivate tomatoes and flowers. A little plant or seed becomes a big thing, and I don’t get how, but it’s amazing. Same in music. So let me try to unravel David Gilmour a bit.  First, progressive rock has been on my mind this week with the passing of Keith Emerson of Emerson, Lake, and Palmer, and now with my experiencing David Gilmour of Pink Floyd fame for two nights at the Hollywood Bowl. As British musician Arthur Brown noted, progressive rock originated in the United Kingdom “as an attempt to give greater artistic weight and credibility to rock music.” It includes such bands as Jethro Tull (my first concert ever), Yes, ELP, and, of course, Pink Floyd. Progressive rock pulses in its own niche, a sound much different than Bruce Springsteen, for instance, whom I wrote about last week. Springsteen delivers short narratives and comments on life, while Gilmour’s songs often have a hypnotic rhythm, searing solos, and ponderous lyrics. With Springsteen, you might experience being down-and-out in a city, yet finding passion or hope to deliver a new destiny. With Gilmour and Pink Floyd, you become what philosopher Martin Heidegger might have hoped for you: present in the moment. Thoughts of your daily life and even your body seem to disappear into feeling the sights and sounds before you. I discovered Pink Floyd in high school in Minnesota. A classmate and musician brought in the group’s fifth album, Atom Heart Mother, and loaned it to me. This was music unlike anything I’d heard—not the standard three-minute singles on the radio. The first side of the LP sailed along as one song, six parts, for over 23 minutes. The other side included “Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast,” a 13-minute piece that mixed people eating breakfast and playing music. On the same side, I loved “Fat Old Sun,” whose lyrics gently looked at a summer in the country with the sun setting, written by Gilmour. The cover of the album had a cow on green grass turning its head to the viewer. The band’s name appeared nowhere on the cover, and you could not find pictures of the band. In fact, I can’t recall ever seeing members of the band on any Pink Floyd album, so I came to think of Pink Floyd as just a thing, a unit.  When I became a senior in high school, my school offered for its first time a chance at independent study, so I made one in filmmaking. I created a Super 8 film that simply rattled off still images—often just four frames at a time—of things that influenced my life at the moment, in sync with Pink Floyd’s song, “One of These Days,” which ran 5 minutes, 57 seconds. The song came from the Meddle album, which I blasted though my quadraphonic sound system. My movie influenced my becoming a film major in college. Later, my love of imagery and sound led me to writing. When I arrived at the University of Denver in 1972, I learned Pink Floyd would play at the school’s arena that week—a good sign. I walked over with my cousin Peter, who attended DU at the same time. (This being 2016, the Internet has the set list from the concert by clicking here.) The band played much of its upcoming album Dark Side of the Moon, which when released in 1973 would become an immediate hit, topping the Billboard charts for a mind-boggling 741 weeks (over fourteen years). Clearly, the album tapped into some of the eternal mysteries of life. My memory of the concert wasn’t about any of the band members, but the use of fog, incredible lighting with colors that changed in a flash, and extended songs that made me float along with words that somehow sounded reassuring. In 2006, my friend Riff Root said he went to David Gilmour’s amazing concert in Hollywood. Root had been the ombudsman at DU, and was now an entertainment attorney in Santa Monica. “Gilmour? Who’s he?” I asked. “You know, the amazing guitarist from Pink Floyd.” As much as I’d liked the band, oddly I never learned who was in it. I did after that. I learned how each member contributed masterfully, too: Gilmour with his guitar and lead vocals, Nick Mason on drums, Roger Waters, who wrote many of the lyrics and played bass, and Richard Wright, the genius at the piano and keyboards. Syd Barrett started with the band but creeping mental illness had him drop out in 1968, and 1975’s album Wish You Were Here was a tribute to him. He died in 2006 of pancreatic cancer. After hearing Riff go on and on about the Gilmour concert in 2006, I vowed if Gilmour ever came back, I would go. It took ten years. My desire was reinforced when I watched the DVD of Gilmour’s concert at the Royal Albert Hall, Remember That Night. (You can see the songs “Breathe” and “Time” from that concert by clicking here. It features Richard Wright on keyboards; he died in 2008 of lung cancer.) I went to buy tickets for the Gilmour concert at the Hollywood Bowl a half hour after tickets went on sale. My high school friend Jim said he’d go with me as my wife didn’t like the band—too “out there.” The concert was already sold out. A second concert was added, and I grabbed tickets. When my cousin John wrote weeks later that he’d fly from Idaho to see Gilmour, I bought a pair on resale for the first concert. Thus, I’d go two nights. That first night, I had high expectations for the concert. John and I found our seats in Section D, right near the center boxes. The lights went out, and fog started filling the stage under a blue light. I became tense with anticipation. Gilmour and his eight-piece band launched into his new album, Rattle That Lock, playing the title track. The performers moved as mere silhouettes in the heavy fog and blue and purple backlighting.  A giant disk that hung from the Bowl’s band shell came to life. The disk had three uses during the night: as a canvas to beam out changing colors, a video screen to show closeups of Gilmour and band members as they performed, and as a screen to show animated and filmed clips to reinforce the music. The disk also featured computer-controlled lights on its outer edge. The first hour brought a combination of Gilmour’s solo work, and the Pink Floyd songs “Wish You Were Here,” “Money,” “Us and Them,” and “High Hopes.” The last featured the Division Bell from the album of the same name. After a short break, Gilmour began with “Astronomy Domine,” a song from Pink Floyd’s first album before Gilmour had joined the group—flowy, eerie stuff, the very thing that loses my wife but I adore. After a brief intermission, the second set brought “Shine on You Crazy Diamond,” “Fat Old Sun,” and seven other tracks. The first evening also included David Crosby of Crosby, Stills and Nash, who joined Gilmour to sing four songs—an extra treat. In many of the evening’s songs, Gilmour could zip into moving guitar solos, often in the high range of notes, yet I never felt he was showing off or proving himself. Still, at age 70, he’s forceful. His solos also never felt as if he were noodling for purpose like a jazz musician trying to find the main thread. Rather, he gave a sense of driving ahead, sure of himself, making each moment count—mesmerizing, bending the strings, pushing his tremolo bar, arcing for the exact notes he needed.  Gilmour ended the second set with “Run Like Hell” from The Wall. The song starts at a fast pace. I sometimes listen to “Run Like Hell” on the treadmill when I exercise. It forces me into an exact 4 m.p.h. fast walk. (I’ve hit the time of life where I need to consciously exercise to keep in shape before I reach that great gig in the sky.) At the concert, “Run Like Hell” offered a frenetic pace of different-colored lights clicking down on Gilmour while the other members played in the dark. The stage lights grew brighter and ever-changing, and each player wore sunglasses. The instrumentation escalated while a chorus sang “Run, Run,” and it all ended in a warfare of fireworks, timed to the fast pace and growing into so many rockets that the Hollywood sky became bright white, as did the stage. How could he top that? Gilmour merely said, “Good-night. Hope to see you again.” He and the band strode off. Of course, no modern concert can merely end like that. In the old days, people would hold lighters aloft while others clapped hard. Now we display lit-up cellphones. The group returned with an encore of “Time” and “Comfortably Numb,” with the disk and the band shell pouring out clock images; the last song offered an array of new lighting effects including reflected lasers that framed Gilmour and shot above the audience. Crosby sang the words to “Comfortably Numb” that first night. The second night was much the same, other than “What Do You Want from Me?” replaced “On an Island” from the first night. The second night let me absorb more, see more, and watch how tightly formed each piece actually is. I felt as satisfied as on the first. It was also fun seeing Jim behold Gilmour live for his first time. He, my cousin John, and I witnessed a portion of rock history. Gilmour, too, reminded me to keep pushing and exploring. As he sings in “Time,” “The sun is the same in a relative way, but you’re older / shorter of breath and one day closer to death.” The concert had to end with “Comfortably Numb” for two reasons. It’s one of a few songs the audience actually knows the words to and sang along. It also offers the line, “There is no pain. You are receding / A distant ship, smoke on the horizon.” Perhaps it’s a comfortable way to think of the end.  When tickets for Bruce Springsteen and the E Street band went on sale in December, I first hesitated. I’d seen Springsteen ten times over the years, starting with The River tour in 1981 at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena. I’d experienced the Born to Run tour twice at the Coliseum in 1985, and I once flew to Denver in 2003 to see him with my cousin Liz (getting an early plane back to L.A. to teach the next morning). He was now touring the same River album and ending the tour at the same Sports Arena—which is scheduled for demolition after this tour. Got to go, I told myself, and I hit my computer and Ticketmaster the moment the tickets went on sale at 10 a.m. While it took a half hour to finally get seats, the moment I tried to pay for them, I received an error message. There was no one to call. I lost out. The place sold out shortly thereafter. When tickets for a second show went on sale a few days later, I tried the phone line as well as the computer, and captured two blocks of six tickets. Thus eleven friends and I went last night. There’s something much different seeing him perform live versus listening to his live shows on Sirius XM radio, I realized last night. What’s missing is the audience. When he sings “Thunder Road,” for instance, so is most of the audience, pumping their collective hands in the air at certain points. When he does “Dancing in the Dark,” most of the audience dances. While he’s often introduced his band much like a gospel minister, suggesting his concerts are a spiritual experience, they are a spiritual experience. His shows often reflect the best of the human condition, the human touch. In The River, a song that caught me off-guard last night was "Point Blank," which has a narrator reflecting on a lost love, "You wake up and you're dyin'/ you don't even know what from." It was one of the softer songs that had a real punch. Springsteen appeared as lost as the character he sang about. The lighting was dramatic, from the side, and the screens near the stage showed him from two different angles, quite cinematic. The words themselves offered a little story, something he's known for. I once obsessed over the song, playing it many times over in a row. Last night it became new again. Few entertainers can be as intimate, especially in a setting like the Sports Arena, which holds over 16,000. He not only often plays right on the edge of the stage, but also last night he took his wireless microphone right into the sea of people in front of him, shaking hands, singing, not missing a beat. From deep into the audience on the floor, while performing “Hungry Heart,” he crowd-surfed, and countless palms and fingers like centipede legs slowly carried him back to the stage where Jake Clemons, the saxophonist who replaced his late uncle, Clarence, pulled Bruce upward while blasting with his sax. This contrasts incredibly the recent Donald Trump rallies where Trump incites violence against protesters, saying that in the good ol’ days, protesters would get beat up. Thanks to such talk, violence has erupted at his rallies, and his recent Chicago meeting had to be called off for worries of mayhem. Trump suggests we need a fascist for a leader. Springsteen leads us another way. The last time I saw him, in 2012, he began his concert with the song “Badlands.” For many of us, we were still feeling economic hard times, and it was as if I heard the opening lyrics for the first time: Light's out tonight Trouble in the heartland Got a head-on collision Smashin' in my guts, man I'm caught in a crossfire I don't understand The audience around me had felt and understood the words, too, and we sang and shouted with him, venting the anger we harbored. Yes, we could “wake up in the night/with a fear so real”—yet in that gathering, no one sucker-punched anyone. No violence. Rather, near the end of the song, we had the same notion as the narrator “that it ain’t no sin/to be glad you’re alive.” In last night’s set, in the supercharged series of songs that came after the twenty-one tunes from The River, he brought back “Badlands,” but this time, the song seemed upbeat, happy, everyone pumping their hands into the air each time the word “Badlands” came up, showing the sense of aliveness and gladness throughout. The same love-of-the-moment worked its way through such songs as “Backstreets,” “The Rising,” “Thunder Road,” and “Shout.” He and his seven bandmates played for three and a half hours nonstop. The whole night essentially looked at the river of life. After all, when he created The River album, it was a younger man’s examination of becoming an adult, exploring love, loss, family, marriage, and more. Yet, now, in revisiting it, he’s adding an older man’s touch to it. After all, two of his bandmates have died in recent years. In fact, with last night’s “Dancing in the Dark,” he brought on stage the daughters of Clarence Clemons and Danny Federici, danced with them, and let them play tambourines for several more songs. In "Tenth Avenue Freezeout," the screens gave a series of shots of Clemons and Federici. I’m reminded of mythologist Joseph Campbell, who said his study of religion and storytelling across human time and cultures led him to believe one thing: “Follow your bliss.” Bliss is the sense of seeking truth, a kind of Eastern notion. As he explained it in The Power of Myth, “If you follow your bliss, you put yourself on a kind of track that has been there all the while, waiting for you, and the life that you ought to be living is the one you’re living…. Wherever you are, if you are following your bliss, you are enjoying refreshment, that life within you, all the time.” Springsteen has followed that bliss, remaining true to it. Other rock legends have been sidelined with addictions and scandals, but Springsteen has kept in shape as well as kept exploring. Like many of us, he’s had huge disappointments, divorce, and depression. When he was much younger, in a contract dispute, he felt the sense his career had crashed just as it started. Still, he kept pushing. Each album has brought him to new places, new insights. That’s what drives me to see him, frankly. He shows the way for all artists: keep looking, keep working, keep exploring. He’s still going strong at sixty-six. His youth wasn’t that long ago. |

AuthorBefore I wrote novels and plays, I was a journalist and reviewer (plays and books). I blogged on Red Room for five years before moving here. CategoriesArchives

July 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed