If there’s one mantra I have for myself in writing and book publishing, it’s “Keep trying new things.” It's not a mere aphorism for me. It's a truth that's worked in several ways. First is in the writing itself. When I began as a writer in college, certain things worked, and others did not--so I kept trying. I accepted I was Charlie Brown, and Lucy would forever yank away the football (but then one day, she did not.) When a story doesn't work, put it aside and try another. Keep trying. As to what to write, some experts suggest to “brand” yourself and don’t vary. If you want to write horror, then write horror, but then don't write a comedy. You're muddling up your brand. However, I've never bought into that. I’ve sensed that my style and voice is my brand. This is to say, I can’t help but see the world as absurd and funny. I come up with serious stories, such as a woman on the verge of suicide in my short story, “I’d Rather Die than Move to North Dakota,” and humor slips in. (It was published by Lit Noir, a literary journal.) My world point-of-view guides my subconscious mind as I write. That allows me to go into different genres and try new things. I have two literary novels out, and now two crime novels, along with two collections of short fiction. I’m trying new things. “Keep trying new things” rose its head again when my most recent crime novel, A Death in Vegas, appeared. I wanted to try a new type of marketing. My books grab readers, but how to get that across to more people? “Let’s try a book trailer,” I said. My publishing company hired a brilliant young Los Angeles director, Samuel Gonzalez, Jr., known both for his short dark films and also for his music videos. We went over basic ideas, which included my reading from the novel. When I showed up for the shoot, Gonzalez had brought in actors for a sequence that riffs a few scenes from the novel. I was to star. I had never thought of myself as an actor. I’m a writer. Something in me said I had to stay true to my work, my baby, my novel, and so Gonzalez guided me brilliantly through the shoot. You can see the film below. He turned the trailer into a mini-movie, which runs seven minutes without the credits. See what you think. In short, if you’re a writer or creator of any sort, push yourself, try new things. Malcolm Gladwell in his book The Outliers says you have to persist for over ten thousand hours until your great at it. Start now. You might like the results.

34 Comments

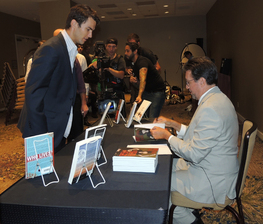

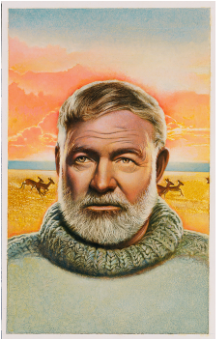

I tried something new a little over a year ago: teaching online. I live and write in California, but agreed to teach creative writing at Southern New Hampshire University via the internet. All started well. My first two classes were great with a dozen interesting and eager students in each class, and I had some latitude in how to teach. To teach online well requires more time than physical classes. It's because you can't see your students' body language or answer things quickly. Most things are written. When SNHU doubled my class size for the third term--to 25 students--and I was forced to give some other professor's writing exercises and readings, which was a lot of busy work for the students and me, it all became crazy. I won't go into it, but I didn't agree to do it again. Even so, I liked the students a lot. I even liked the medium. If you're looking for online classes in writing, look for small classes such as at UCLA Extension. One thing I wished to try for the third class was to be more visual. I created small videos for my class, which worked out well. This led to another type of video, one for the general public on how to make it big in writing: getting rich-rich-rich from your efforts. After all, that's what I'm often asked: How do you get rich in writing? I answer it here. Click below for my surefire tips to get there. It’s short, just four-and-a-half minutes.  When I first started writing, I aimed to be a “serious young writer,” which is why after working as a stock clerk at a Hollywood camera store and then as a tile salesman in Los Angeles’ San Fernando Valley, I joined an MFA writing program at USC. I adored my time at the university and made good friends. We were all serious young writers, ready to storm the Bastille of Mediocrity, beat aside bad agents, and deliver the Truth. Some of us were there to write the serious and artful Great American Screenplay along the lines of Five Easy Pieces, M*A*S*H, The Deer Hunter, and The Conversation. Others, who cared nothing for money, wanted to write the next great play, our generation’s Death of a Salesman or Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolff? I would later write Who Lives?, a story about who might be among the ten test subjects of the first working kidney dialysis machine. Some of my friends wanted to crack the novel in a fresh way, such as was done with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and whatever Tom Wolfe was doing with New Journalism, which seemed novelistic. Witness The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Me, I wanted to write movies, plays, and novels—and throw in short stories and essays. The great thing when you’re young is you don’t have to put a governor on your ambitions. None of us in the program were short of dreaming. The one thing we did NOT want to do was write in a genre, such as writing horror or a thriller. Genre was selling out—just not dreaming big enough. Influential books at the time for me included Watership Down by Richard Adams, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Persig, and Sophie’s Choice by William Styron. I didn’t read Stephen King’s books of that decade, which included Carrie, The Shining, Salem’s Lot, and The Dead Zone. That’s because Stephen King was in the horror category, a genre I didn’t want to consider. I also assumed (wrongly) that King must not be a very good writer if he was always writing horror. Then a few years ago, I read some of his short stories including the one that became the movie The Shawshank Redemption. The stories, touching, revealing, full of emotion, and well-written, blew me away. When his book 11/22/63 came out, I had to see his take on the Kennedy assassination because I remembered the day vividly. I was in fifth grade when Kennedy died. I saw all the adults around me cry, and my parents were Republican. I became glued to King's 11/22/63. After I finished it, I moved onto his Joyland. I found it gripping and emotional. These two novels made me appreciate King’s writing and also see many of the things he probably learned early on, things which have taken me many years of writing plays, screenplays, and novels to see. Because I also teach creative writing, these are some of the lessons I try to get across to my students. I should explain both novels briefly. In 11/22/63, 35-year-old English teacher Jake Epping learns that his friend’s diner in Maine has a time portal in the back room that takes any traveler to a date in 1958 at that same place. No matter how long you stay away, you return two minutes after you left. After Epping tries it a few times, he realizes he could drive down to Texas, hang around five years, and then try to stop Lee Harvey Oswald from killing JFK. Joyland is both coming-of-age and a mystery set in 1973. Twenty-one-year-old Devin Jones's heart is broken by his college girlfriend, who runs off with another guy. Each day, Devin is consumed by the loss, but after he takes a summer job at an amusement park in North Carolina and comes to know his co-workers, he slowly mends. He also gets curious about a murder that happened in the park a few years earlier, and there's a rumor that her ghost can be seen on one of the rides. Using Joyland and 11/22/63, I offer a few things I’ve come to appreciate about King’s writing. 1) Devin Jones in Joyland and Jake Epping in 11/22/63 are great protagonists. Jones is vulnerable and temporarily damaged—and I deeply empathized with him. Epping not only has tremendous curiosity for when he finds a wormhole into the past, but also he realizes he can expunge one great evil—Oswald—and perhaps change history for the better. Both these characters are driven, and readers clearly see their goals and desires. 2) Truth. One of my own goals in my work is to meter out truthful moments. I’m not so much going after the Big T Truth, but it’s the little ones that count, moments that reveal life as we know it. King does this as easily as breathing. For instance, in Joyland, Jones says, “People think first love is sweet, and never sweeter than when that first bond snaps. You've heard a thousand pop and country songs that prove the point; some fool got his heart broke. Yet that first broken heart is always the most painful, the slowest to mend, and leaves the most visible scar. What's so sweet about that?” Later Jones realizes, “It’s hard to let go. Even when what you’re holding onto is full of thorns, it’s hard to let go. Maybe especially then.” In 11/22/63, Epping says, “We never know which lives we influence, or when, or why.” Later he adds, “Stupidity is one of the two things we see most clearly in retrospect. The other is missed chances.” We also come to learn and understand another truth, “The past is obdurate.” When I write, I’m on the lookout for moments when such truths can lend the story extra depth. 3) Foreshadowing is hard to do, but when done well, it gives any story a sense of destiny and the tone of “This happened; you have to hear this.” One reason it’s difficult to create foreshadowing is that you have to know your own story well. If you’re on a first draft, you may not know what will happen fully. You can’t foreshadow it yet. Thus, foreshadowing is something I tend to add in later drafts. In both of King’s books, the foreshadowing lends foreboding. Also, the narrator indicates he’s older than the events, and he’s relating what has come to dominate his memory. This gives a sense of importance to the stories. 4) Dialogue and details. King has the right balance for both—not too much or too little, which sets the pacing. “I started to reply,” says Jones about the fortuneteller. “She hushed me with a wave of her ring-heavy hand.” 5) The biggest thing that originally stood in my way of appreciating genre fiction was the idea that genre was devoid of theme. Perhaps I thought that literary stories considered theme and all other stories didn’t. Theme, however, is everywhere. Even writers who don’t think about theme tend to have one because where a story ends says something. You can have the richest, most empathetic characters, but if in the end they are all brutally murdered, that’s suggesting something about life, no? I never thought of Raymond Chandler as genre because the plots of his detective stories were all over the map—but Philip Marlowe’s insights, tone, and themes grabbed me. That should have clued me in that genre could be special. My wife tends to watch what I call “bludgeoning shows,” things like Dateline or 20/20 where the true-life tales are often about one spouse murdering another and then trying to hide it. A theme that comes through is “Spouses lie and murder, and marriages are horror shows.” While that’s certainly a truth out there, it’s not one I want as universal or paramount. Theme at its best is a truth that weaves through a story and can be sensed in the end. Good writers somewhere along the way come to understand what their stories are about and then make readers or viewers discover it on their own. King is a master of this. In both Joyland and 11/22/63, you’re in good hands. I'm now a King fan, even if I haven’t read most of his books. I love these two and I’m starting a new one, Lisey’s Story, because he said in an interview, he felt it was his best one. Truth be told, now that I’ve written two crime novels, Blood Drama and A Death in Vegas, I have an extra appreciation of genre. In theme, I’ve strived to make the books more than bludgeoning shows. They are about the human condition, including its joys and absurdities. Good stories are hard to create, and as a writer, I have to celebrate good ones when I see them. In my off hours, I’m enjoying Bosch, which streams on Amazon. There’s another genre writer I enjoy: Michael Connelly. That’s for another blog. -- Note: NPR interviewed King about how he writes. Read/hear that interview by clicking here.  Ernest Hemingway Ernest Hemingway When I took my first creative writing class, a poetry class, in college at the University of Denver, I did it because I needed to fill in some credit hours. English had never topped my hit parade because most of my professors had made me feel that to truly understand a book, you needed to be an English major. I was not. I was into psychology. Little did I know then that psychology would be important in reading and writing. My last required English class, one in American Literature, turned me around. I couldn’t believe that in Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, the protagonist, Jake Barnes, was impotent—although I didn’t know that word then. I surmised, though, that his penis somehow didn’t work right, and could we really be reading about this in a class? Was it legal for a writer to write about that? How were we going to talk about it? I learned that Hemingway had traveled to Spain in 1925, and a lot of those experiences such as the running of the bulls had ended up in his book. He’d had a few wives, so apparently impotence wasn’t a problem. Maybe it was when he killed himself on July 2, 1961. After that, I also discovered that an F. Scott Fitzgerald story that we read, “The Rough Crossing,” was based on a trip that Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda had taken. I hadn’t known until then that it wasn’t cheating for writers to draw from their lives so directly. Also in “The Rough Crossing,” I was impressed how the storm at sea matched the storm in the characters’ marriage. That was a clever thing. When I took the poetry writing class, I drew from my life, as did many of the other writers in the class, and it was fun. Symbols emerged in some of the poems, which could add extra meaning. I learned of other poetic devices, such as alliteration and onomatopoeia. This word stuff was amazing. Another important event in my life was that I spent part of my junior year abroad in Denmark. I learned about language in a whole new way: if you don’t know a language, it’s difficult to communicate. In high school, I’d taken Spanish and Latin, but because Minnesota didn’t have many people speaking either language, I never felt any urgency to learn. In Denmark, I really wanted to understand what people were saying around me. I took Danish, and I came to see that understanding another language also gives you clues to how a large group of people think. After all, language guides our thinking. Danes have some dozen words for “snow,” yet they have the same word for “fun” and “funny,” which to us are two different concepts. There, I also spent a lot of time reading English-language novels that I picked up in a local library because I had a lot of time to myself. I’d never been much of a reader until that point. Books were incredible. How had I missed that before? I’d discovered Kurt Vonnegut’s books in Denmark, and while the story lines were wild and of science fiction, much truth rang out to me. In Cat’s Cradle, for instance, Vonnegut created words for things that had no previous words. A “karass” is group of people linked in a cosmically significant manner, such as those in a Corvette-owners club. A “duprass” is a karass of two: two people who are so deeply connected, they are their own universe. They often die within a week of each other. I read voraciously abroad. I remember looking for the thickest book in English at the Danish library. It was Of Human Bondage by Somerset Maugham. I read it on buses, trains, everywhere. Wow. After college and a few years of jobs selling things such as men’s clothes, cameras, and ceramic tile, I went on to earn an MFA in creative writing. In 1994, I started teaching creative writing at CalArts after I’d been publishing a lot of articles and reviews and writing short stories and plays. One thing most creative writing classes don’t have time for is reading published stories and books. Nonetheless, I would slip in a few. Why reinvent the wheel when writers before us have done some amazing things? Reading great stories gives you permission to experiment. In my third year of teaching, the chair of the English department at Santa Monica College called me out of the blue, having heard I was an inspirational instructor, and she asked had I considered teaching English? I hadn’t, but I took up her offer. My challenge was, “How do I stir my future students in English a way that most of my English professors had not?” The main thing that had turned me off was in reading older books about older characters that I had no connection to. I thought I’d use contemporary nonfiction narratives and novels, trying new things every semester, one by a female author, one by a male, to keep me on my toes. It has worked. I assign the reading and a few questions to go with it, and my students and I sit in a giant circle and discuss it, like a book club. Everyone talks. I also instruct them how to read more actively. Reading with a pen in hand helps. They should underline or highlight things that speak to them. If they have a question about something, write it in the margin. The first time a major character is introduced, put a bracket around it. For example, J.K. Rowling in the first Harry Potter book introduces Hagrid with “hands the size of trashcan lids” and feet “like baby dolphins.” When you write in your book, you interact with it. You make it your own. If it’s your book, you can write in it. I delight when students—and it happens often—say something like, “I’ve never been a reader, and I didn’t think I’d like reading this, but I couldn’t put it down.” One student told me, “It’s weird. It’s like a movie in my mind. I’m looking at ink on a page, and suddenly I’m in these people’s lives. I love it.” I’ve used such books as Patti Smith’s Just Kids, about her years after high school in New York, and she and Robert Mapplethorpe struggled to find what to do with their lives. Novels such as In the Lake of the Woods by Tim O’Brien and Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake worked well. Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five had only a lukewarm response, but his Cat’s Cradle found converts. I’ve ended up creating a list on Amazon’s Listmania of the most successful books I’ve used, which you can see by clicking here. These are books that engaged nonreaders, and you may enjoy them too. Many of my students are surprised they like reading and want to know how to find more books. With perhaps two million books published each year, there absolutely are new things you will love. You just have to find them. Services such as BookBub, BookGorilla, and BookSends help you discover new books at bargain prices. They send you a handful of links to highly rated books each day whose eBooks are on sale. Choose the category of books you like, and in this daily email, you are likely to find things that grab you. I know I’ve ignited a number of students into reading. Reading helps a person think, feel, and see the world in fresh ways. It may inspire you to write, and writing draws you into thinking and understanding more deeply. May you find the frenzy of reading. Reading is life.  When I was ten, my parents gave me a telescope, and I formed an astronomy club. Suburban Minneapolis had the benefit of many stars. As my four friends and I met one evening at sunset, ready for the blanket of stars, the full moon slipped up over the horizon and surprised us. The huge dish radiated bigness—bigger than the moon was normally—and one of us said, “Hey, it’s Mars, and it’s off its course. What if it crashes into us?” We were convinced Mars had slipped out of line, and no one but us knew about it. We hopped on our bikes and rode toward this orb quickly as if we could get closer and examine it better. We pointed skyward. “Mars! It’s definitely Mars!” This moment hangs as a symbol to me of what it is to be a writer today. One is that there are many misguided things to do that suck up your time, money, and attention. The second is that marketing definitely has its own gravity and is a giant moon in your life. One of the joys of taking a creative writing class in college or elsewhere is that you’re focused on the creative process, not on marketing. You are building your skills. At that point, commerce may as well be Santa Claus—it doesn’t seem real and, if anything, will bring you the gift of a career. Don’t count on it. Readers search for great stories told well. They have to find your work, though, and that takes marketing. You need it. Today’s writers, if they aim for sales, have to become practical and put aside the “fun, creative part” to promote what they have. What follows are some truths I’ve learned about the planet of creativity in harmony with the moon of marketing. 1) Don’t rush into marketing less-than-polished work. Everyone and her taxi driver are writing books. If you truly think your book has a place in the marketplace, engage your talented friends or hire a professional editor to get your book to be the best. 2) Book publishing is intimidating. That’s why agents and big publishers still exist—because if you’re talented, and you want to stay focused more on the writing than on the marketing, this traditional route still works. To get an agent requires writing a query letter—which has to be some of the best writing of your life. After all, you’re proving your worth in a page. 3) If you go the self-published route, know in advance that you have to become a master of marketing. You can hire services or people to help you with the self-publishing process, but beware of services that promise you the moon. You can spend thousands of dollars to little effect. If you didn’t seriously take my first point, polishing your work, no one is going to buy your book. An amateurish book design or less-than-stellar book description will hobble your book more. 4) Self-publishing can work. It takes dedication, starting with polishing your book. You learn that self-promotion isn’t singing “Buy my book” in a loud voice on social media, but rather, you do a lot of indirect things, such as joining the community of writers by writing a blog, writing book reviews, advertising, hiring a blog tour operator, and more. It’s all ever-changing, so keep reading about this stuff. The fact you’re reading this is a good sign. 5) The challenge of marketing can be addicting. It’s fun to watch something that you did sell a thousand books in a day. Don’t let it override your main goal, which is to write books with merit. 6) One less-obvious step to get you thinking and immersed in marketing is to attend a writing conference. To get a taste of one, see my previous post or click here. May your planet and moon circle with success.  Writers often tend to keep to themselves, but the biggest convention of writers is the annual AWP Conference--the Association of Writers and Writing Programs--which will take place April 8-11 this year in Minneapolis. I thought I'd offer this from last year's conference to give you a taste. -- Imagine a three-day film festival in a giant complex where you had a selection of 33 movies every 90 minutes, and each of the 500 movies would be shown only once. Add to that more than 12,000 attendees vying for the choices over the three days. That gives you an inkling of what it felt like to attend the 2014 Conference for the Association of Writers and Writing Programs (AWP), held in 2014 in Seattle. Attendees received a thick catalog detailing the more than five hundred panels, and panels changed every 90 minutes. The panels could be divided into categories. There were those that addressed publishing and getting published, either through traditional methods or other ways such as do-it-yourself. There were panels that addressed ways of teaching creative writing, such as using the stories of Flannery O’Connor in the classroom. Then there were voyages of how to write creatively, such as research strategies for creative nonfiction or using an unusual point of view such as from a dog. Academic explorations examined such things as passive characters in contemporary fiction and poetry as a philosophical foray. Last, there were readings of poetry and fiction. If a person could absorb two or three panels a day, catch a reading, meet a friend for lunch, and attend the Book Fair on the fourth floor of the Seattle Convention Center, that was a big day. The Book Fair featured more than 600 exhibitors competing for your attention, offering handouts, chocolates, raffles, and glimmers of publication. One could meet editors of journals for future submissions or examine some of the more than 200 MFA writing programs across the country. Then there were the hundreds of off-site meetings and parties. To zoom from 9 a.m. to 11 p.m. each day took much stamina. To find a moment of rest and pleasure was difficult—until I found that short story writer Rick Bass, who lives in Montana, would be reading his stories, accompanied by live music. The band Stellarondo, named for the character in Eudora Welty’s “Why I Live at the P.O.”, had composed original scores to go with Bass’s stories. The AWP Convention, by the way, is the only convention I’ve liked. Years ago, I’d been to a few Comdex computer conventions in Las Vegas—miles of walking indoors to see the latest programs, computers, and gadgets. I’d been a delegate to the Modern Language Association, but would be lucky to find three panels among its hundreds of offerings, most of them professors dryly reading papers to other professors. I arrived for Rick Bass at 10:30 a.m. to a giant ballroom filled with chairs and a stage up front, to find only twenty people, and the band was just setting up. I went up to one person and said, “This is all there is? I thought this would be the coolest thing at the whole convention.” “Me, too,” she said. “I don’t get why it hasn’t started yet or why more people aren’t here.” I went up to a band member to learn the show was at noon. We’d misread the catalog. Thus, I grabbed a cab to the waterfront to visit the Seattle Mystery Bookshop on Cherry Street, then zipped back in time to see the performance. Rick Bass sat in a comfortable chair on stage that had a microphone. The band spread out to the right of the stage, and the four members prepared their instruments: pedal steel guitar, acoustic and electric guitars, banjo, cello, glockenspiel, musical saw, upright bass, and vibraphone. The lights dimmed, and the magic began, first with the band playing what might be called mood music, and then Rick Bass starting in on his story “The Canoeists.” While I instantly loved the idea of music and words, one thing worried me: that the music might overwhelm the stories. Instead, the music offered a gentle flow, allowing Bass to pause at certain sections, and he didn’t have to start up right away. The music filled the space and let you think about the words you just heard. At times, the band members would take turns playing, so that there would only be one soothing sonic sense at a time. Together, they mingled in harmony. After the first story, Bass told the audience that he had had doubts when the band first suggested a collaboration. He pictured beat poets with bongos, and he said that had rarely been effective. “However, working with these musicians,” said Bass, “I learned what Barry Lopez meant about ‘stories need to have space.’” Now when Bass writes, he pictures the aural space his words might have. I sat in the front row and let the music and words drift over me, and everything was about the story. I was in the moment as when I ski. I was present. It was now. Each story unfolded at its own pace. Bass read two more stories, “Fish Story” and “The Bear.” When it was over and the lights came up, the woman next to me and I looked at each other and said “Wow” in tandem. To get a taste of Bass with music, the band has clips on its website, which you can hear by clicking here. After the show, they were selling CDs of Bass’s stories with music, but the line became quickly long, and I had to get to the airport. Still, the show was the perfect way to end AWP. I’ve since learned one can get the album here.  “Literary” is a type of book many people admire, but it’s not a genre that people necessarily seek. It’s even hard to call it a genre the way “mystery,” “romance,” and “paranormal” might be. Books that appear on Amazon’s literary best seller list, for example, reveal how widely defined “literary” really is. For instance, this week, number one is Paula Hawkin’s novel, The Girl on the Train, a psychological thriller along the lines of Gone Girl. Yet it’s also under “literary” in three spots in the Top Ten, for Hardcover, Kindle, and Audio versions. Also on the list is Elizabeth Hall’s Miramont’s Ghost, a ghost story partly set in France in 1884 and in present day Colorado. Tan Twan Eng’s A Gift of Rain is sixth on the list and it takes place at the end of World War II, on the lush Malayan island of Penang, focusing on a young man caught in a web of wartime loyalties and deceits. It neatly fits into historical fiction. It’s also “literary.” These join the list with Harper Lee’s soon-to-be-released Go Set a Watchman, a sequel to To Kill at Mockingbird, definitely literary. Still, in my mind, what all the novels here share is good writing, and they’re stories about interesting, even ordinary people. I wrote my two collections of short stories and my first two novels without any thought of genre or being “literary.” All my stories simply revolve around some huge problem that comes to an otherwise ordinary person. I put pressure on my characters and then look to see what they do. As one of my mentors, playwright Robert E. Lee, co-writer of Inherit the Wind, said “plot is nothing more than following what interesting people do.” When it came time to market my first books, they were marketed as “literary.” However, my last two novels are crime books. I fully understood I was writing in a genre. I didn’t study the genre to be a copycat and fit some steely paradigm. I do read the genre, though. A mystery novel, at its core, has to have a murder and a mystery about who did it. There have to be dead ends. Still, that didn’t stop me from making my protagonist, Patton Burch, in A Death in Vegas, an interesting man. Patton runs a beneficial bug business for organic gardeners, and when the gorgeous and smart model he hired to be a lady bug for his booth at a Las Vegas convention turns up dead in his hotel room, and the police focus on him, he breaks off to solve the mystery and clear his name. I knew going in, I had to have surprises, but there’s something about the way I see the world—it’s absurdity—that still slips in. If writing rich characters and coming up with certain truths about life is literary, then that’s what I’m still doing, but within the mystery genre. I have to say, when I was in the MFA writing program at USC—and then later I taught there—we never focused on “literary” or any genre, for that matter. We just focused on writing stories. Of course, in hindsight, I think it could be helpful to aspiring writers to understand genre and what they’re writing so if they’re aiming for certain readers, you can meet their expectations while meeting your own. If you’re as an eclectic reader as I am, then you’ll have similar tastes in what you think of as a good novel. Off the top of my head, I’ve loved Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad, the non-linear Pulitzer Prize winning story of a group of intersecting characters, including a record producer. I thoroughly enjoyed and recently taught in my English class The Yellow Birds by Kevin Powers, which takes place in Iraq and is a different story than the one I’m writing. I also love rereading The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler, a detective novel, which my wife is reading now. All can be considered literary. Shelly Lowenkopf in his fabulous The Fiction Writer’s Handbook, which offers an understanding of hundreds of terms that writers use, defines “literary story” as “a prose narrative written to discover a feeling, intent, or meaning; an exercise of the writer’s curiosity to see where the problem will lead and whence the solution—if any—will come; a prose narrative in which the writer knows the conclusion or believes the provisional conclusion is, in fact, the conclusion, then retraces in order to clarify the obstacle.” I can guarantee few if any writers start out writing a novel saying, “Let me figure out an ending and then I’ll retrace it to clarify the obstacle.” Such a definition is more of what an agent, publisher, or critic might think in trying to analyze a story. In fact, Lowenkopf dives into what a writer often does, which is begin the literary story “with a dramatic construct located beyond his ability to see an easy way out.” A literary story, he says, “is a contract made by the writer not to write anything safe.” I love that point because with anything I ever write, even if I create a detailed outline (and I do so for novels), I’m never sure if my story will work. Will it meet my initial hopes for it? I write many drafts until it works. Surprises happen as I write, so that I have to dive back into my outline and change things. My outlines have their own lives. They are not etched with a chisel in granite. I know some book reviewers in the future might try to figure out the path I’ve taken to what I write and publish. For instance, the novel I’m now writing is a first-person war novel that takes place in Iraq in 2007, and how does that fit in with my other novels? I’ll let readers figure it out. My novels include a protagonist who is a film producer, another who’s a top quantum physicist, one who is a graduate student writing a dissertation on playwright David Mamet, and now in A Death in Vegas, my beneficial bug guy. All I can say is to jump in and hold on for an experience. If that’s literary, that’s what I do. I love doing it--a perfect declaration today for Valentine's Day. Happy Valentine's Day.  For the last ten years in my college class in children’s literature—where the students have to write their own stories for children—I’ve had my students read J.K. Rowling’s first Harry Potter book, Harry Potter and the Sorceror’s Stone. It grounds them in many ways. I originally wrote this three years ago, but it’s worth bringing back. -- I love Harry Potter and the Sorceror’s Stone not only for how it surprised me when I first read it, but also for how it’s been inspiring my students. Is Harry Potter and the Sorceror’s Stone the richest, most meaningful book to use? Not necessarily. My 13-year-old daughter is reading To Kill a Mockingbird, and that’s closer to my heart. The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold, The English Patient by Michael Ondaatje, and Water for Elephants by Sara Gruen are a few of the adult books I adore. Yet there’s much to admire and learn from J.K. Rowling if you’re a writer. Here are a few things: 1) It’s important to get the overall sense and feel of the series to learn why people would stand in a long line for a day to buy one of the books. Wouldn’t you want people to stand in a line for your book? 2) More specifically, you can learn how concise Rowling’s descriptions of people can be with a well-placed simile or two. She describes Hagrid’s hands as “big as trashcan lids and his feet in their boots were like baby dolphins.” Fabulous. 3) Humor is throughout the first book. You’d never know it by the first movie, but the book is hilarious at times—and very dark toward the end. Humor can be mixed with drama. How humor can grab kids is important to know, too. I put a check mark in the book by things I thought were funny, and the pace of her humor is interesting. You sense that Rowling had fun writing the book. 4) As the series goes on, Harry is a year older in each book, and the reading level and darkness grows. Understanding who your primary readers are is important. 5) It’s nearly impossible to stop reading at the end of a chapter because you have to know what happens next. That’s an important element for writers to learn. 6) Rowling is a master of structure in the first book because when we first meet Harry, he’s passive, and the main antagonist, Voldemort, doesn’t come into action until much later in the book. That’s a prescription for a dull book, yet each chapter has tension if not outright conflict. Thus you, the reader, may not notice Harry isn’t the most interesting character. He grows into that role. 7) Notice, too, there are plenty of other antagonists before and after Voldemort appears. There are Harry’s aunt and uncle, who treat him poorly. Their son Dudley and his pals bully him. When Harry gets to Hogwarts, there’s Draco Malfoy and his cronies Crabbe and Goyle to rain on his parade, and many of the professors, especially Snape and those who teach the Defense Against the Dark Arts classes, stand in his way. There’s also internal conflict with Harry. He’s not always sure he can do things. 8) Notice that Harry isn’t the lone warrior like Superman or as in most male-oriented stories. Harry has help from his friends Hermione and Ron Weasley. In fact, sometimes the stories objective narrator slides off with them for short stretches. The fact that Harry has friends and the fact that Hermione is so strong as a young woman opens the door to girls liking the story, too. 9) None of the characters are perfect, which rounds them out. Many people hate Hermione at first because she seems to be such a know-it-all, yet she grows on you. Harry, as mentioned earlier, is at first passive, and throughout the series, he has doubts. He’s also remains true to his instincts and into doing the right thing, even if the rules are against him. In psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg’s stages of moral development, Harry is an evolved being. 10) I rarely read fantasy, yet I never thought of the books as fantasy when I first read them. They seemed so real that I accepted the magic stuff. How does Rowling do it? The details are right. A flying broomstick isn’t merely a broomstick, but a Cleansweep Seven or a Nimbus Two Thousand. Hogwarts feels exactly like sixth grade felt to me way back when, with bullies on the playground and teachers who were either helpful or scary. Populate your book with truths. People will then buy the imaginary. These observations are things that spoke to me. Even though my own new novel, Love At Absolute Zero is an adult book about a scientist looking for love, I’ve used the above. My protagonist, Gunnar Gunderson, is far from perfect. He has friends to help him in his quest. There are strong female characters including his mother and his friend Ursula. There are plenty of antagonists, too. The details of science are real, but so are the human interactions. The pacing is strong. In short, I had fun writing the book, and it’s a funny story. If you’re a writer, there’s much you can admire from Rowling. May people stand in line for your books.  A few years ago, Kirkus Reviews, commissioned me to write an article on how I found success in publishing doing it “my way.” It’s worth reprinting here for the larger font. (You can see it at their website by clicking here, even if it now mistakenly says I’m “Malcom Gladwell, interviewed by Christopher Meeks.) To paraphrase President Bill Clinton, how I did it depends on the definition of “it.” I’m a writer first, and an accidental publisher second. What drove me to do either is that I wanted meaning in my life. The other night, my wife Ann and I zipped over to the Hollywood Bowl, invited at the last minute by a friend with extra tickets. It felt like destiny. I witnessed for my first time cellist Yo-Yo Ma play and Gustavo Dudamel conduct—both brilliant, both passionate, both having me ponder what it took for them and any one of the orchestra members to get there. A sell-out crowd of 17,000 was focused on classical music. Yo-Yo Ma played often with his eyes closed, his face incredibly expressive as if the music were telling a story and he was finding surprise and amazement in every twist and turn. He seemed near tears in delicate parts, his lone cello a voice in the woods. Conductor Gustavo Dudamel looked like a young man surprised at a treasure he stumbled upon. He was ecstatic to unleash the kettle drums, the trumpets, and the full orchestra as a signal call to a final offensive stand, his baton and hair leaping in the air. There are times when I write that I feel the same way. I‘m emotionally wrought at sad parts, laughing at funny parts, on the edge when danger flings itself at my protagonist. What it took me to get there were the hundreds of stories that I wrote when I was younger that just didn’t work, but each story brought me closer to writing a better one. I took writing classes in college and beyond, and I was pushed. Reading great works such as Tim O’Brien’s book The Things They Carried showed me what could be. I never thought of what I did as “work.” As Malcolm Gladwell’s book Outliers reveals, you have to put in the hours. I value what I do. That’s the first place that counts. Sometimes people who discover one of my short story collections or novels write me out of the blue to say how much they loved it. These I treasure as much as the brightest critics finding joy in my work. To get where I am took more than reading, practice, and classes. I also looked for ways to immerse myself in story. I became a book reviewer in grad school for two Los Angeles newspapers before reviewing live theatre for Daily Variety for eight years. At the time, I was also writing plays. Theatre demonstrated how to reveal character through action and dialogue, and the constant critiquing led me to question why certain scenes or plays worked or not. I’d ask the same questions of my own stories. I wrote on tight deadlines, which whipped away any idea of writer’s block. Later when I started teaching creative writing and English, I could critique student work too, remaining sensitive to not blow out any flames of creativity. For my first job out of grad school, I was the senior editor for a small publisher in Los Angeles, and I experienced first-hand the obsessive nature it takes to create a finely crafted book, starting with the text but also following through in book design, publicity, and marketing. Thus when my first agent in 2005 did not want to represent my collection of previously published short fiction, I started my own imprint, White Whisker Books. I knew what to do. When my very first review for my first book, The Middle-Aged Man and the Sea, appeared in the Los Angeles Times in January 2006, I spit the cereal I was eating out all over the table. My heart began racing. I assumed I’d be excoriated in front of millions of people as had happened with my first produced play, Suburban Anger. But no, the reviewer gave clear specific insights, and she celebrated the book. I don’t write for the reviewers, but good reviews help in being discovered in a crowded marketplace. Sending your books out for review is critical. This I learned when I worked for a publisher. I call myself the accidental publisher because White Whisker Books was conceived simply for my short fiction. Later, I published my novels when my enthusiastic new agent, Jim McCarthy at Dystel and Goderich, found roadblocks. For Love At Absolute Zero, he landed three interested editors whose marketing departments then vetoed the book. Apparently love and quantum physics was a leap. Undeterred, I published it through White Whisker, and it landed on a critic’s Top Ten Best Novels list of 2011, and it earned three awards including being a ForeWord Reviews Best Book Finalist. Small victories like these help. White Whisker Books has grown as I can fit in time for it. I’m publishing three other authors now whom I know and respect. I hire editors, proofreaders, and book designers. I make advance reader’s copies for reviewers as I did recently for The Fiction Writer’s Handbook by Shelly Lowenkopf. I create flawless eBook versions of the books in multiple formats. I use social media, write emails and blogs, speak at conferences and colleges, and, if I’m lucky, I write articles such as this for Kirkus. Those people who want to know, “How do I do it so I can get rich?” all I know is you don’t get any success if your heart isn’t in the work. In the arts, you compete with people who have passion for what they do, the Dudamels and Mas. Much of success is persistence. That’s not everything, though. It’s not like the Hollywood movies where if you’re dogged and passionate, you’ll win. There are plenty of conductors, cellists, and writers who are extraordinarily talented, but they are not recognized. Look at this another way. Art schools and creative writing programs pour out hundreds of extremely talented graduates each year to a society that doesn’t value the arts, per se. Only a few of these graduates will make a name. Are you still willing to push ahead if fame or fortune is not guaranteed? If so, the arts may be for you. “How to make it?” That’s something you might learn along the way. -- Update: The front page article in today’s Los Angeles Times covers what it takes to be a musician in the Los Angeles Philharmonic, which underscores much of what I wrote here. Click here and scroll down for the story. I’ve since published two well-reviewed crime novels, Blood Drama and A Death in Vegas. I’m now at work on a novel based in the Iraq War. As you see, I go where my interests take me.  Not so many years ago, one of my former students, April Davila, wrote and asked if I’d write a blog on a particular subject, “writing and parenthood,” and I thought I’d bring this one back. This one resonates for me as my son, now 27, yesterday was asking about my novel-in-progress, which happens to take place in Iraq. April wrote me that she’s due to give birth soon and asked if I’d be a guest blogger. I happened to be one of her professors at USC in the Master of Professional Writing Program. Her request brings up the one subject that is rarely whispered about yet alone spoken of in graduate writing programs: how do you write once you become a parent? Parenting, too, is on my mind because I’m seeing the whole life cycle right now with my mother dying just a few weeks ago. I suppose that puts me in the batter’s circle for the next up to the plate, though I feel young and healthy and my daughter’s twelve and I just came back from a parent-teacher conference and I’m not ready to bat. I don’t want to even be in the ballpark. If you’re in a writing program, it’s all you can do to write that novel, biography, memoir, play, screenplay, television show, collection of poetry, or creative nonfiction book. You don’t want to hear about more demands on your time and attention. You don’t want to learn the big secret no one told us when my wife and I brought our newborn son home twenty-three years ago: babies don’t sleep through the night. We became zombies for almost a year. In short, your life is forever changed. Yet you soon feel the luckiest person in the world. You’ll be amazed at how personality shows up within weeks. After a year, you’ll have witnessed your baby becoming a person, and you won’t be able to put your finger on when it happened. This little creature, brimming with curiosity, is learning all the time and so are you. Your nonparent friends will get quickly bored by each new thing you’ve seen, and in another few years, you’ll be making new friends: the parents of your child’s best friends. You’ll be buying birthday cakes and booking clowns. I can also say your writing will grow and become richer and more important. I happened to recently interview my own former professor, David Scott Milton, and I asked him how his children has affected his life as a writer, and he said, “It may be obvious, but it’s nevertheless true, that you are not fully human until you have kids. There are aspects of being a human that don’t resonate or flourish until you have kids of your own. I remember as a young man finding Shakespeare’s King Lear the least satisfying of his great tragedies. Years later, when I had kids, the play moved me more than anything Shakespeare had written." Milton went onto say, "I realized that only a father could have written it as Shakespeare had. The love, the confusion, the pain, the connection we have to those we have helped bring into this world is profound, even shattering. When Lear cries over his daughter Cordelia’s body, it is monumental and can only be fully felt I think by someone who is a parent.” I will also tell you do not forget two things: your spouse and your goals in writing. You and your partner need to give exclusive time to each other, and going out a minimum of once a month sans baby if not every few weeks is mandatory. If you’re not maintaining your relationship, it’ll suffer easily. As much as you will at first hate to find a babysitter, find one. Your writing needs to remain important, too. It’s easy to feel guilty when you’re writing that you’re not being a good mother or father. It’s also easy to say, “I’ll do it when he sleeps through the night … when he goes to preschool … when he graduates high school … when I become a grandparent.” Writing needs to be as important as spouse and baby. Before I had children, I’d made a specialty of interviewing authors for newspapers and magazines, and one of my first interviews was with Chaim Potok, who’d written The Promise and The Chosen. I’d asked him, “How do you manage to write with children in the house?” and he said something like, “Writing is something I’ve always done, and so my children have grown up knowing that’s what I do. They’ve learned not to disturb me while I’m writing unless it’s an emergency.” I have to say that while my children have grown up seeing that I write, I take the Starbucks approach. I can work amid a lot of hubbub and coffee. I also learned from screenwriter David Franzoni (Amistad, Gladiator), who told me he awoke at five a.m. to write for a couple of hours before the household awoke. The first few days of trying that, I thought I was insane. I wanted to be in bed. Yet my son and wife would sleep until seven, and I found those two hours before I had to help with breakfast and go off to my full-time job were the most productive of the day. I wrote more than professional writers I knew who had no children. In fact, you learn how to write efficiently when you have the time. April happened to ask me about this less than an hour ago, and so I’ve written it on the spot, wedging it in before my dentist appointment and picking up the cat from surgery. My mother happened to encourage me to write and had been proud of my books. She’d just finished rereading my novel The Brightest Moon of the Century days before she fell and broke three ribs, and falling again led to her demise. When I went into her bedroom after she passed, I found the diary I’d given her last year in hopes she’d write about her life. She had written only one page in it during the whole year, and it was dated “Father’s Day 2009.” She wrote of her sons that, “They all turned out to be good fathers. Chris is realizing it’s good to be strict.” Well, I’m stricter than I started out. Your children will feel more firmly grounded when they know the clear rules that you abide by. And a rule for yourself: keep writing. Find the time when he or she naps or goes to bed for the night or before anyone wakes up in the morning. You will flourish. |

AuthorBefore I wrote novels and plays, I was a journalist and reviewer (plays and books). I blogged on Red Room for five years before moving here. CategoriesArchives

July 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed