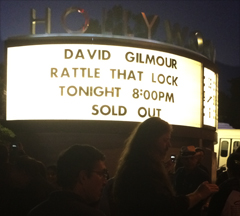

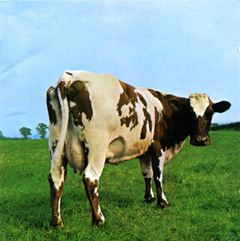

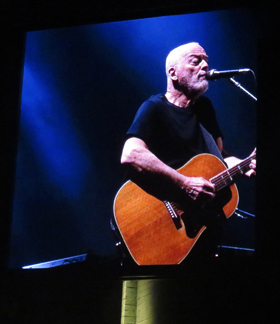

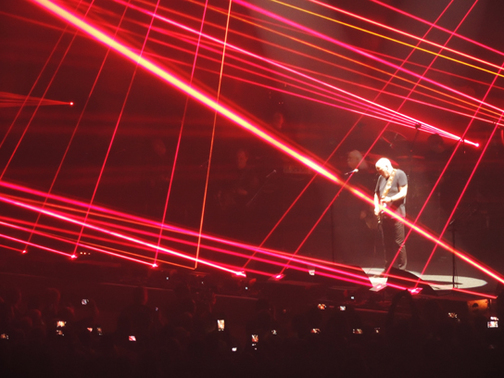

I’ve been going to rock concerts more steadily over the last few years. It’s something I did in high school, yet now that I’m older, I ask myself why now? It’s a rediscovery of the mystery of music. I’m not clear how great music works, or how people make it, yet I sense it’s similar to why I write fiction. For me, writing does several things. By slamming different characters and situations together, I witness people struggle, trying to attain whatever their goals are, much as I am. Sometimes, like me, they are also trying to understand things. Yet there’s also the mystery I love in writing. I’m never sure if a story will work out—and sometimes it doesn’t—but I’m curious to see what will grow. As author Rick Moody wrote after his novel The Ice Storm, “Sometimes I think words are so beautiful so flexible so strange so lovely that they make me want to weep, for the import, for their proximity to eternal mysteries.” Maybe it’s also why I cultivate tomatoes and flowers. A little plant or seed becomes a big thing, and I don’t get how, but it’s amazing. Same in music. So let me try to unravel David Gilmour a bit.  First, progressive rock has been on my mind this week with the passing of Keith Emerson of Emerson, Lake, and Palmer, and now with my experiencing David Gilmour of Pink Floyd fame for two nights at the Hollywood Bowl. As British musician Arthur Brown noted, progressive rock originated in the United Kingdom “as an attempt to give greater artistic weight and credibility to rock music.” It includes such bands as Jethro Tull (my first concert ever), Yes, ELP, and, of course, Pink Floyd. Progressive rock pulses in its own niche, a sound much different than Bruce Springsteen, for instance, whom I wrote about last week. Springsteen delivers short narratives and comments on life, while Gilmour’s songs often have a hypnotic rhythm, searing solos, and ponderous lyrics. With Springsteen, you might experience being down-and-out in a city, yet finding passion or hope to deliver a new destiny. With Gilmour and Pink Floyd, you become what philosopher Martin Heidegger might have hoped for you: present in the moment. Thoughts of your daily life and even your body seem to disappear into feeling the sights and sounds before you. I discovered Pink Floyd in high school in Minnesota. A classmate and musician brought in the group’s fifth album, Atom Heart Mother, and loaned it to me. This was music unlike anything I’d heard—not the standard three-minute singles on the radio. The first side of the LP sailed along as one song, six parts, for over 23 minutes. The other side included “Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast,” a 13-minute piece that mixed people eating breakfast and playing music. On the same side, I loved “Fat Old Sun,” whose lyrics gently looked at a summer in the country with the sun setting, written by Gilmour. The cover of the album had a cow on green grass turning its head to the viewer. The band’s name appeared nowhere on the cover, and you could not find pictures of the band. In fact, I can’t recall ever seeing members of the band on any Pink Floyd album, so I came to think of Pink Floyd as just a thing, a unit.  When I became a senior in high school, my school offered for its first time a chance at independent study, so I made one in filmmaking. I created a Super 8 film that simply rattled off still images—often just four frames at a time—of things that influenced my life at the moment, in sync with Pink Floyd’s song, “One of These Days,” which ran 5 minutes, 57 seconds. The song came from the Meddle album, which I blasted though my quadraphonic sound system. My movie influenced my becoming a film major in college. Later, my love of imagery and sound led me to writing. When I arrived at the University of Denver in 1972, I learned Pink Floyd would play at the school’s arena that week—a good sign. I walked over with my cousin Peter, who attended DU at the same time. (This being 2016, the Internet has the set list from the concert by clicking here.) The band played much of its upcoming album Dark Side of the Moon, which when released in 1973 would become an immediate hit, topping the Billboard charts for a mind-boggling 741 weeks (over fourteen years). Clearly, the album tapped into some of the eternal mysteries of life. My memory of the concert wasn’t about any of the band members, but the use of fog, incredible lighting with colors that changed in a flash, and extended songs that made me float along with words that somehow sounded reassuring. In 2006, my friend Riff Root said he went to David Gilmour’s amazing concert in Hollywood. Root had been the ombudsman at DU, and was now an entertainment attorney in Santa Monica. “Gilmour? Who’s he?” I asked. “You know, the amazing guitarist from Pink Floyd.” As much as I’d liked the band, oddly I never learned who was in it. I did after that. I learned how each member contributed masterfully, too: Gilmour with his guitar and lead vocals, Nick Mason on drums, Roger Waters, who wrote many of the lyrics and played bass, and Richard Wright, the genius at the piano and keyboards. Syd Barrett started with the band but creeping mental illness had him drop out in 1968, and 1975’s album Wish You Were Here was a tribute to him. He died in 2006 of pancreatic cancer. After hearing Riff go on and on about the Gilmour concert in 2006, I vowed if Gilmour ever came back, I would go. It took ten years. My desire was reinforced when I watched the DVD of Gilmour’s concert at the Royal Albert Hall, Remember That Night. (You can see the songs “Breathe” and “Time” from that concert by clicking here. It features Richard Wright on keyboards; he died in 2008 of lung cancer.) I went to buy tickets for the Gilmour concert at the Hollywood Bowl a half hour after tickets went on sale. My high school friend Jim said he’d go with me as my wife didn’t like the band—too “out there.” The concert was already sold out. A second concert was added, and I grabbed tickets. When my cousin John wrote weeks later that he’d fly from Idaho to see Gilmour, I bought a pair on resale for the first concert. Thus, I’d go two nights. That first night, I had high expectations for the concert. John and I found our seats in Section D, right near the center boxes. The lights went out, and fog started filling the stage under a blue light. I became tense with anticipation. Gilmour and his eight-piece band launched into his new album, Rattle That Lock, playing the title track. The performers moved as mere silhouettes in the heavy fog and blue and purple backlighting.  A giant disk that hung from the Bowl’s band shell came to life. The disk had three uses during the night: as a canvas to beam out changing colors, a video screen to show closeups of Gilmour and band members as they performed, and as a screen to show animated and filmed clips to reinforce the music. The disk also featured computer-controlled lights on its outer edge. The first hour brought a combination of Gilmour’s solo work, and the Pink Floyd songs “Wish You Were Here,” “Money,” “Us and Them,” and “High Hopes.” The last featured the Division Bell from the album of the same name. After a short break, Gilmour began with “Astronomy Domine,” a song from Pink Floyd’s first album before Gilmour had joined the group—flowy, eerie stuff, the very thing that loses my wife but I adore. After a brief intermission, the second set brought “Shine on You Crazy Diamond,” “Fat Old Sun,” and seven other tracks. The first evening also included David Crosby of Crosby, Stills and Nash, who joined Gilmour to sing four songs—an extra treat. In many of the evening’s songs, Gilmour could zip into moving guitar solos, often in the high range of notes, yet I never felt he was showing off or proving himself. Still, at age 70, he’s forceful. His solos also never felt as if he were noodling for purpose like a jazz musician trying to find the main thread. Rather, he gave a sense of driving ahead, sure of himself, making each moment count—mesmerizing, bending the strings, pushing his tremolo bar, arcing for the exact notes he needed.  Gilmour ended the second set with “Run Like Hell” from The Wall. The song starts at a fast pace. I sometimes listen to “Run Like Hell” on the treadmill when I exercise. It forces me into an exact 4 m.p.h. fast walk. (I’ve hit the time of life where I need to consciously exercise to keep in shape before I reach that great gig in the sky.) At the concert, “Run Like Hell” offered a frenetic pace of different-colored lights clicking down on Gilmour while the other members played in the dark. The stage lights grew brighter and ever-changing, and each player wore sunglasses. The instrumentation escalated while a chorus sang “Run, Run,” and it all ended in a warfare of fireworks, timed to the fast pace and growing into so many rockets that the Hollywood sky became bright white, as did the stage. How could he top that? Gilmour merely said, “Good-night. Hope to see you again.” He and the band strode off. Of course, no modern concert can merely end like that. In the old days, people would hold lighters aloft while others clapped hard. Now we display lit-up cellphones. The group returned with an encore of “Time” and “Comfortably Numb,” with the disk and the band shell pouring out clock images; the last song offered an array of new lighting effects including reflected lasers that framed Gilmour and shot above the audience. Crosby sang the words to “Comfortably Numb” that first night. The second night was much the same, other than “What Do You Want from Me?” replaced “On an Island” from the first night. The second night let me absorb more, see more, and watch how tightly formed each piece actually is. I felt as satisfied as on the first. It was also fun seeing Jim behold Gilmour live for his first time. He, my cousin John, and I witnessed a portion of rock history. Gilmour, too, reminded me to keep pushing and exploring. As he sings in “Time,” “The sun is the same in a relative way, but you’re older / shorter of breath and one day closer to death.” The concert had to end with “Comfortably Numb” for two reasons. It’s one of a few songs the audience actually knows the words to and sang along. It also offers the line, “There is no pain. You are receding / A distant ship, smoke on the horizon.” Perhaps it’s a comfortable way to think of the end.

1 Comment

When tickets for Bruce Springsteen and the E Street band went on sale in December, I first hesitated. I’d seen Springsteen ten times over the years, starting with The River tour in 1981 at the Los Angeles Memorial Sports Arena. I’d experienced the Born to Run tour twice at the Coliseum in 1985, and I once flew to Denver in 2003 to see him with my cousin Liz (getting an early plane back to L.A. to teach the next morning). He was now touring the same River album and ending the tour at the same Sports Arena—which is scheduled for demolition after this tour. Got to go, I told myself, and I hit my computer and Ticketmaster the moment the tickets went on sale at 10 a.m. While it took a half hour to finally get seats, the moment I tried to pay for them, I received an error message. There was no one to call. I lost out. The place sold out shortly thereafter. When tickets for a second show went on sale a few days later, I tried the phone line as well as the computer, and captured two blocks of six tickets. Thus eleven friends and I went last night. There’s something much different seeing him perform live versus listening to his live shows on Sirius XM radio, I realized last night. What’s missing is the audience. When he sings “Thunder Road,” for instance, so is most of the audience, pumping their collective hands in the air at certain points. When he does “Dancing in the Dark,” most of the audience dances. While he’s often introduced his band much like a gospel minister, suggesting his concerts are a spiritual experience, they are a spiritual experience. His shows often reflect the best of the human condition, the human touch. In The River, a song that caught me off-guard last night was "Point Blank," which has a narrator reflecting on a lost love, "You wake up and you're dyin'/ you don't even know what from." It was one of the softer songs that had a real punch. Springsteen appeared as lost as the character he sang about. The lighting was dramatic, from the side, and the screens near the stage showed him from two different angles, quite cinematic. The words themselves offered a little story, something he's known for. I once obsessed over the song, playing it many times over in a row. Last night it became new again. Few entertainers can be as intimate, especially in a setting like the Sports Arena, which holds over 16,000. He not only often plays right on the edge of the stage, but also last night he took his wireless microphone right into the sea of people in front of him, shaking hands, singing, not missing a beat. From deep into the audience on the floor, while performing “Hungry Heart,” he crowd-surfed, and countless palms and fingers like centipede legs slowly carried him back to the stage where Jake Clemons, the saxophonist who replaced his late uncle, Clarence, pulled Bruce upward while blasting with his sax. This contrasts incredibly the recent Donald Trump rallies where Trump incites violence against protesters, saying that in the good ol’ days, protesters would get beat up. Thanks to such talk, violence has erupted at his rallies, and his recent Chicago meeting had to be called off for worries of mayhem. Trump suggests we need a fascist for a leader. Springsteen leads us another way. The last time I saw him, in 2012, he began his concert with the song “Badlands.” For many of us, we were still feeling economic hard times, and it was as if I heard the opening lyrics for the first time: Light's out tonight Trouble in the heartland Got a head-on collision Smashin' in my guts, man I'm caught in a crossfire I don't understand The audience around me had felt and understood the words, too, and we sang and shouted with him, venting the anger we harbored. Yes, we could “wake up in the night/with a fear so real”—yet in that gathering, no one sucker-punched anyone. No violence. Rather, near the end of the song, we had the same notion as the narrator “that it ain’t no sin/to be glad you’re alive.” In last night’s set, in the supercharged series of songs that came after the twenty-one tunes from The River, he brought back “Badlands,” but this time, the song seemed upbeat, happy, everyone pumping their hands into the air each time the word “Badlands” came up, showing the sense of aliveness and gladness throughout. The same love-of-the-moment worked its way through such songs as “Backstreets,” “The Rising,” “Thunder Road,” and “Shout.” He and his seven bandmates played for three and a half hours nonstop. The whole night essentially looked at the river of life. After all, when he created The River album, it was a younger man’s examination of becoming an adult, exploring love, loss, family, marriage, and more. Yet, now, in revisiting it, he’s adding an older man’s touch to it. After all, two of his bandmates have died in recent years. In fact, with last night’s “Dancing in the Dark,” he brought on stage the daughters of Clarence Clemons and Danny Federici, danced with them, and let them play tambourines for several more songs. In "Tenth Avenue Freezeout," the screens gave a series of shots of Clemons and Federici. I’m reminded of mythologist Joseph Campbell, who said his study of religion and storytelling across human time and cultures led him to believe one thing: “Follow your bliss.” Bliss is the sense of seeking truth, a kind of Eastern notion. As he explained it in The Power of Myth, “If you follow your bliss, you put yourself on a kind of track that has been there all the while, waiting for you, and the life that you ought to be living is the one you’re living…. Wherever you are, if you are following your bliss, you are enjoying refreshment, that life within you, all the time.” Springsteen has followed that bliss, remaining true to it. Other rock legends have been sidelined with addictions and scandals, but Springsteen has kept in shape as well as kept exploring. Like many of us, he’s had huge disappointments, divorce, and depression. When he was much younger, in a contract dispute, he felt the sense his career had crashed just as it started. Still, he kept pushing. Each album has brought him to new places, new insights. That’s what drives me to see him, frankly. He shows the way for all artists: keep looking, keep working, keep exploring. He’s still going strong at sixty-six. His youth wasn’t that long ago. |

AuthorBefore I wrote novels and plays, I was a journalist and reviewer (plays and books). I blogged on Red Room for five years before moving here. CategoriesArchives

July 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed