|

If you’re a writer, you probably don’t (or shouldn’t) think of yourself as average—because to write well is an extraordinary thing. If you’re not popularly read yet, well, you can consider Van Gogh, who only sold one painting in his lifetime. Or perhaps you’re akin to California writers John Fante or Phillip K. Dick, writers whose genius was affirmed after they died. However, if you want to be published and recognized now, you might observe the reality of the book business and work up from there. Publishing has changed dramatically over the last decade with the rise of self-publishing. Who reviews books and how books are promoted have changed. Here are a few things to consider. First, we’ll start with money. 1) A handful of unknown authors have become superstars from self-publishing. This is both about talent and luck—luck akin to the lottery. If you want to learn how this happened, click here on stories of Hugh Howie and Darcie Chan. For the most part, though, consider that when you start out, you might make, if you’re talented, a few hundred to several hundred dollars per year. Will you write even if there are not a lot of financial rewards? A survey by Digital Book World shows the reality: hybrid authors (who are both traditionally published and self-published) earn the most money, with a median income between $7,500 and $9,999 a year, followed by traditionally published authors ($3,000–$4,999), and self-published (indie) authors ($500–$999). Most indies I know make much more than this, which I'll get to at the end. It's about having a platform. These statistics are the median, which includes those who quickly drop out. Many authors, self-published or otherwise, feel they’ve made it if they’re in bookstores. Bookstores, however, have to compete against eBooks and online bookstores. It's hard to get into bookstores--and do you really want it? 2) Bookstores make their money on bestsellers, naturally, and most authors are not best-selling. Therefore, if your book is stocked, it’s often NOT with the cover facing but with the spine facing. How often do you find new authors from just seeing the spine? Books that are displayed spine only tend not to sell. 3) Bookstores can get their money back from publishers by returning books that don’t sell. Bookstores use specialized software to track every title. Books that don’t sell in 30 days are often returned. Thus, your books are likely to be returned—which is expensive. There goes some of your royalties. 4) Books that DO sell at bookstores are often not automatically reordered unless a large number have been sold. Thus, the shelf life of a new book is not very long—perhaps a couple of months in total—unless you’re a well-known author. 5) Barnes and Noble closed 223 stores last year. They have 640 left. For the last four years, people have been predicting the chain’s demise. They keep trying new things, including selling more than books, but you have to ask yourself WHY do you go to a bookstore? I have two reasons: to pick up a copy of a well-known book, such as one I might be teaching, or to discover a new title or author. I tend to go to independent bookstores for the latter, as the employees often have special shelves for their recommendations. As a chain, I like Barnes and Noble. I’ve read in some. I don’t want to see them go away. For mid-list books, however, especially older ones, I’m forced to buy online. Literary agents have changed, too. Gone are the days where an agent and publisher groom a new writer when they see talent. That’s how Hemingway and Fitzgerald started. Agents now get ten percent of what their authors make, so they need to find what they think will be popular authors. If your book ideas don’t sound commercial, don’t expect agents will even call or write back. Here are the new realities: 6) Editing. Publishers, trying to keep costs down, look for amazing stories that need little editing. Both agents and editors look for stories that are ready or nearly ready to be published. Thus, you the writer need to consider hiring a professional editor to have your book in top shape. As a writer, you may be spending a few thousand dollars on your book in hopes of recouping it. You need great editing whether you're self-publishing or sending it to an agent. 7) Agents. Literary agents are more difficult than ever to find because they’re swamped with queries, and the clients they have now are often more-and-more difficult to place. My last agent, Jim McCarthy at Dystel and Goderich in New York, believed in me. He sent Love at Absolute Zero to more than forty editors, and three of them sent him letters that went something like “I loved Meeks’s novel—very funny. I stayed up much of the night and laughed often out loud. He’s talented. However, the marketing department said no, that it’s too hard to market a book about science and love.” In the end, I published it myself and found, yes, it is hard to market, but it won awards and found its niche. In short, you’re more likely to have correspondence with a major celebrity than with an agent. Still, I’m convinced a brilliant query letter about a brilliant book will find an agent. As the publisher of a handful of authors—I have a very small press—I’ve come to a few realizations: 8) Printed books can be a drain. That’s because of my third point, above, that the books are probably shown spine out. How many of the 640 Barnes and Noble and over two thousand independent bookstores can you get to and make sure your book is bought and displayed well? The more awards and better the reviews a book gets, the more I sell to bookstores—and the more returns I get. One of my author’s books received a Los Angeles Book Festival Award, and the returns were so high a few months later, I’m in the red on it still nearly a year later. I’ve now made my books non-returnable, and bookstores are not buying. They won’t if they can’t return it. 9) Bookscan. As I was looking for a new agent, one wrote me immediately with a printout from Bookscan, the company that tracks sales of printed books. These days, most of my sales are in eBooks, because, as I said above, printed books are a drain. Still, I sell some printed books. Publishers and agents want to see high numbers from Bookscan. Thus, I’ve realized, if you as a self-published author do not offer a printed version of your book with a scanable ISBN number, then as far as a publisher and agent are concerned, your book is unpublished—which is good if you want at some point to be published by a major publisher. If that doesn’t concern you, then Createspace, an Amazon company, makes it easy to have printed books. 10) Your platform. Probably the best thing you can do if you’re marketing yourself is to not expect a runaway hit. Rather, look for ways to inch ahead. It’s about volume and making a small percentage on volume. The idea is to find your fans and potential readers and create a database of them. When you have a new book, you can write to them directly. The person best known for this is English author Mark Dawson, who essentially discovered that old-fashioned advertising in a high-tech way gets you there. A Forbes article (click on his name above or here) details how he earns nearly a half million dollars a year from Amazon alone. Basically, he writes a really good novel, has it well-edited and proofed, and then using mostly Facebook ads, aims it at the right audience. While his advertising costs add up after a while, so does his income. Some of his critics think it’s lame. If you have to spend $10,000 to bring in $12,000 of income, you only clear $2,000. Now add a zero to each number and understand his approach. If you’re curious about this, he offers three free lessons in what he does. If you need more hand-holding, he offers more for a nominal price. I’ve tried the free three lessons and am inspired. (Click on “three free lessons” above.) I don’t make anything from this—it’s just my own free advice. The main thing to understand in all this is today’s writer also needs to be a promoter and marketer. Best to you this year.

1 Comment

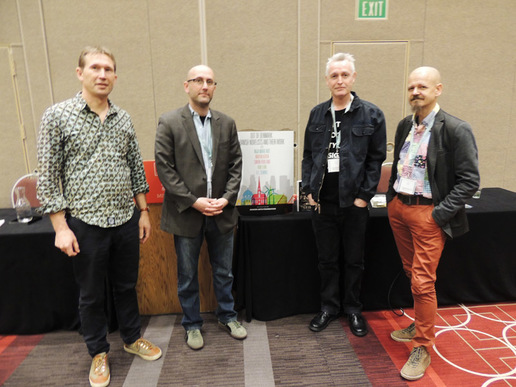

Since May 2014, I’ve been working on a novel, The Chords of War, mostly set in the Iraq War, collaborating with my former student Samuel Gonzalez, Jr., who served in Iraq. The novel is inspired by his time there as well as his years as a rock musician. An interesting thing happened with this manuscript, which we’re still working on—nearly done. Producer Ed Pressman (American Psycho, Wall Street) optioned Sam’s life rights and tapped Sam to direct the screenplay now being written. Pressman also optioned my novel. This may sound more golden than it is. Sam or I won’t see any money until the financing is secured, and the film goes into production. Still, I hope the option will make publishing easier. I’m looking for a new agent. We’re on the sixth draft. What makes working with Sam, a director, so interesting is Sam has a powerful visual sense and a natural touch for drama. If you never saw the short film he made of my mystery, A Death in Vegas, click here. For those of you following the books I publish, you might say I’m eclectic. Some writers choose a genre and stick with it. From a marketing standpoint, that makes sense, particularly if the books are in a series. As a reader, if you want a Michael Connelly novel, you’ll buy a taut police procedural with Detective Harry Bosch or his Lincoln lawyer, Mickey Haller. If you’re into YA dystopia, you may read Suzanne Collins and her Hunger Games series. In contrast, I grew up reading whatever grabbed my interest, and I’ve followed suit in my writing. In high school, I worked in our paperback book store at lunch, and it was there I discovered the fiction and poetry of Richard Brautigan and the science fiction of Ray Bradbury. In English classes, we read Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, which seemed eclectic to me. In college, I read John Updike and Kurt Vonnegut, and after college, I explored more and found such great writers as Margaret Atwood, Janet Fitch, Alice Walker, and Nick Hornby. I started writing short stories because that’s what one did in creative writing classes. It was there I learned my voice came with humor. Once I discovered I didn’t have to cut out the funny stuff, I became more comfortable with my voice. After I published a number of short stories, I collected them in The Middle-Aged Man and the Sea and then Months and Seasons. My first agent didn’t think there was any money in short fiction and pushed me onto my first novel, The Brightest Moon of the Century, inspired by my years at the University of Denver and beyond. Then came Love at Absolute Zero after novelist Caroline Leavitt thought my real story of zipping off to Denmark for love in college was hilarious. I updated it by making it about a physics professor in the present instead of a college kid in the seventies. It would let me slip in what I knew about teaching. I also saw a weird connection between the laws of physics and the laws of love. My next two novels, Blood Drama and A Death in Vegas, were crime stories with average guys forced into extraordinary situations. I wanted to write something not based on my life, and a thriller or mystery would also help me explore form. My idea was to write a page-turner. There’s a lot to learn about storytelling when you want your reader not to put the book down. I enjoyed writing them a lot—but not enough to make either into a series. That’s because several forces all came together. As a writer, I’ve always kept my eyes and ears open; the universe is trying to tell me something. As a reader, I fell in awe with the work of Tim O’Brien, particularly his fiction in The Things They Carried. I’d been in the last year of the draft for Vietnam, and I wondered how my life might have been different if my birthdate showed up as one of the first ten ping pong balls in the lottery instead of #229. Reading O’Brien gave me a clue. His writing felt honest, truthful, and emotional. A friend then gave me The Yellow Birds by Kevin Powers, set in the Iraq War. I liked it so much, I used it in an English class. Our class discussions had been fabulous. Just after that, I happened to meet Sam Gonzalez for lunch, and he told me of his experiences fighting in Iraq. He asked if I’d consider writing a novel about it. I liked the idea a lot, so we’ve collaborated. What makes this book different from my previous ones is I’m not taking inspiration from my life but from another’s, Sam’s. As a film director, Sam isn’t wedded to what happened to him exactly but more toward what he felt. In O’Brien’s story “Good Form,” O’Brien speaks of happening-truth and story-truth, and how getting the sense of what it felt like versus who really did what is more important. That’s what we’re aiming for in this book—the truth of what it felt like to be there from the standpoint of young men and women who joined because of the hype, the patriotism, or even just a need for a job or to get away. Iraq was not Vietnam. It’s more chilling because America should have learned from Vietnam, but our politicians threw us into Iraq and Afghanistan more because we had the machinery for it. Those who volunteered did not necessarily know any of the politics, but they had to live with it and experience war. Even if you don’t get injured, war can play with your head. I started writing the book in the third person, but Sam rightly felt the first person gave it more presence. Only the prologue remains in the third person. Our protagonist, Max Rivera, played rock before joining the Army, and even if he doesn’t know it, it’s his music that keeps him grounded, especially through the worst of times. Through his friendships and affairs (women are in his platoon), he learns more than he signed up for. Sam understands the power of imagery, and as he reads what I write, he loves the lyricism I’ve delivered and even pushes for more. “More poetry” is his refrain. For me, every day on the book feels important. The word entertaining isn’t what drives me, but You’ve got to read this does. I’ve written far more scenes than we’ve used. In fact, it’s these later drafts where we’ve realized we need to bring some things back. It’s built with two storylines: before the war, and during the war. This is all to say, this book, as with my earlier ones, has come from trying things out, experimenting, moving things around, taking things out, putting things back, pushing for the right tone and similes. I don’t work with a formula but with what feels right and truthful. I’m excited by it. It’s as if the lens of my life has focused on this particular book. I’d like to say writing the fifth book was so much easier than the others—it hasn’t been—but it’s still what I love to do. I feel new each book out. What happens from here, I’ll let you know. (The photo at the top is of Samuel Gonzalez, Jr.)  To film aficionados, the year 1939 was tops in terms of quality. The studio system owned the theaters, had stars under contract, and hired novelists to write films—not that I wish for the system back, but the control proved useful that year. For the year 1939, we had such greats as Gone with the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, Stagecoach, Wuthering Heights, Gunga Din, Dark Victory, Goodbye Mr. Chips, and many more. Here at the end of 2015, I’m in awe. I can’t remember a year where nearly every movie I went to was great. Of course, I chose well, but the fact there’s so many to choose from astounds me. I've seen many gripping films in the last two months: Room, Sicario, Brooklyn, The Revenant, Spotlight, Carol, and The Martian. In fact, after I saw Brooklyn, for a few days I did not want to see another film because that one, about a young Irish woman moving to Brooklyn in 1959, was just so subtle and powerful, I did not want it diluted by an inferior film. Add to that, some stellar movies I caught earlier in the year: Mad Max: Fury Road, Ex Machina, The End of the Tour, Steve Jobs, The Walk (Frenchman on a high wire between the twin towers), and Woody Allen’s Irrational Man. While Allen’s film was far from perfect, the ending was so damn good, it made up for everything. This is all at a time when the blockbuster is king. We’re witnessing Star Wars: The Force Awakens now, and add to that the mostly summer superhero films and various action films such as Fast and Furious. There’s an audience for action and superheroes. (Is that what people see in Donald Trump?) Aside from Mad Max, how do these smaller films not only get made, but get seen? This gives me hope—that people want to witness and consider the human condition. Maybe they’ll bring their down-to-earth attitude to the polling booth in 2016. Part of me thinks such quality films are propelled in part with the enormous offering of quality television, and filmmakers have to match that or be better. My wife Ann and I are watching an incredible six-part series on Netflix called River, about an older British police detective who has recently lost his partner on the force, a middle-aged woman named Stevie. Like a schizophrenic, Detective River still sees Stevie and talks to her, but others witness him talking to the thin air—and that he’s going crazy. Yet he has to find Stevie’s killer. He’s OCD about it while convincing others he’s fit to work. I just finished watching the second season of the FX series Fargo—a near perfect series as there can be. It has the same Coen Brother sense of the dark and absurd, and it’s gripping. This year, we also binge-watched Rectify, about a man wrongly convicted at nineteen for raping and killing his girlfriend. Now after nineteen years on death row, having his execution stayed three times, he’s let out and has no tools for living. It’s on Netflix and Amazon. We also enjoyed on Netflix all seasons of The Killing and Bloodline. I know we’re missing many other great series and movies, but there only so many hours in the day. Besides, I’m OCDing on my own novel, The Chords of War. Still, I wouldn’t mind getting to another few films in the next few weeks. Any recommendations? I heard Trumbo, The Big Short, and 45 Years are special. Note: If you're a short story fan, my award-winning collection, Months and Seasons, is only 99 cents as an eBook for a short while. Click here for Kindle. Click here for all other platforms on Smashwords.  In “Harrison Bergeron,” Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.’s short story about an imagined future where everyone is equal, smart people have a device planted in their heads to balance them with normal people. The gizmo sends out a sharp sound about every twenty seconds—a siren, gunshots, glass shattering—to break one’s train of thought. We are now there. Fewer and fewer of us are able to focus for long before a beep or ring pulls our attention away. That’s particularly hard if you’re a writer. The evidence has been rising around me, but of course I haven’t been paying attention. I might be in a café when a phone at the next table rings, and everyone at my table reaches for his pocket. I then notice the four people at the next table, all of them on their smart phones, are not talking to each other. Once we realize it’s none of us being called, our conversation goes something like this: My friend to my right says, “What were we talking about?” “I was going to look up an actor on IMDB, but I forgot who,” I say. “Wasn’t it Gregg Henry?” “No, that was earlier when we were talking about binge watching The Killing.” “What’s The Killing?” someone else at my table says. Another example: I pick up my daughter from school, but she doesn’t see me because she’s texting. I honk. She gets in the car, says, “Hi,” then is back to texting. If one of her friends is with her, the friend sits in the back, texting, too. I don’t like texting as I’m not fast, and correcting all the mistakes, adding all the punctuation after proofreading, slows me down, but this thought evaporates when my phone rings. It occurred to me in the courthouse the other day—a place where I and other potential jurors had to have our devices off—that we are addicted more than we know. Day after day as I left the court, I and every juror switched on phones, and we walked like zombies, trying to catch up with email or phone messages. If my fellow jurors were cigarette smokers, too, they’d light up first—so phone addiction is just below nicotine addiction. Even if you don’t answer your vibrating phone or the little beep that says you have a text message, the notification alone disrupts your thoughts in a big way, according to a new study from Florida State University. In fact, part of the study observed people trying to write when they received a notification. The study says of writers, “Their productivity will likely be negatively impacted.” (“Negatively impacted” makes me laugh. I’d say “lessened,” but— RING!) I feel it in my own work. As I started this, my phone beeped, and the New York Times informed me of a senseless shooting where a reporter on air was murdered along with a videographer. Are there too many crazies with guns in this country? Why do we have six times rate of gun deaths compared to Canada—fifteen times compared to Germany? See what I mean? I’m off focus. I remember twenty years ago writing my play Who Lives?, and I wrote all day every day, having a first draft in a few weeks. Nothing interrupted me. Now I’m able to get such concentration only in the morning, keeping my cell phone in another room usually. Novelist Jonathan Franzen in an interview with Oprah Winfrey, says that his goal is “to produce a book that can stand up to the noisy culture, that will suck you away from all the distractions that we’re bombarded with.” He does so by isolating himself. “The main thing is no internet, no telephone at the office.” In his quiet office, he thinks about the things that make him the most uncomfortable, things that he doesn’t normally want to think about. He hopes that those things are a reflection of the culture. The trick in my mind is who is in control of my computer and phone? If it’s me, then I need to regulate them. I know I get distracted from even a mere beep, so even if I can’t go a full day without the internet and phone, then the morning is fine. Lately, too, I’ve tried driving without the radio or phone or anything talking at me—just the sounds of the road. Soon, my thoughts roam elsewhere. I’m free. What do you do to concentrate? Do you have time to read without distractions? In celebration of my novel Love at Absolute Zero reaching four years old recently, it’s being sold for $2.99 on Kindle. The novel itself reminds me of being “centered”—I wrote it with amazement in me. To be an artist is what this column is about.

-- Because I teach creative writing at the Art Center College of Design as well as at Santa Monica College, I’m teaching an art in a nation where it's difficult to make a living in the arts. My son happens to be studying computer science, and there are many jobs in it. He will be able to apply to places. Medicine, law, physics are some of the many other subjects where finding a job is clear. To make a living as a writer is not cut-and-dried. I see two general paths for a writer. One is to research and see what types of writing pay the most. When I go onto Kboards’ Writers’ Café, an area where fiction writers publishing eBooks hang out, I see that the best-selling writers fall into the genres of thrillers, romance, and erotica, among others. At the Writers’ Café, you can read first-hand accounts of what small publishers and self-publishers are doing. In short, if your goal is to make money writing, then select a genre and learn it well. You’re not writing for yourself, per se, but writing to fill a market need. You’ll be competing with people who are passionate about their genre. Then there’s the path I took. Most people who get MFAs in writing programs go this way, too: not concerned with genre, but in seeking certain truths about living. Their stories might fall into a genre, but more likely than not, they’ll straddle genres or fall into the “literary” category, which is a catch-all. One truth is if you choose this path, you’re not likely to make money. Still, the most popular books seem to be ones where the writer was not concerned with money or marketing but writing the best and most truthful book possible. For instance, I got to know Janet Fitch at the University of Southern California when we both taught at the now-defunct Master of Professional Writing Program. Like me, she started as a journalist and learned about deadlines and writing all the time. Then she started exploring poetry and incorporating sound and rhythm into her fiction, which started getting published. As she said, “I always read poetry before I write to sensitize me to the rhythms and music of language. Their startling originality is a challenge. I like Dylan Thomas, Eliot, Sexton. There are parts of White Oleander which use cadences of Pound.” Her first novel White Oleander landed her on Oprah Winfrey’s show and in Winfrey’s Book Club. The book became a major hit and a 2006 film. Her last novel, Paint It Black, will also soon be a film, directed by Amber Tamblyn. In a Salon article from 1999, Fitch talks about the twenty-two years it took to become a best-selling author. Much of it is luck. “Luck” isn’t a great way to plan a career, but this is where “centering” comes in. Centering is about what drives you as an artist. If you write for acclaim, then your fortunes will rise and fall with positive and negative reviews. If your goal is for a lot of money—rare in the arts—then your motivation will dry up when funds only trickle in. I think of composer Phillip Glass, whose music I often listen to as I write, who drove a cab for a good chunk of his life as he composed. Composing is what he loved to do, and his style did not, and does not, sit easily with everyone. (For a sample of his work, click here.) Only after his opera Einstein on the Beach made a name did he start getting enough commissions to live on. After teaching at a few colleges including CalArts, Santa Monica College, USC, and Art Center, I’ve come to know a number of faculty in writing, dance, film, theatre, music, and the fine arts, and most of them have made modest names for themselves if not more. All have one thing in common: they are centered on their art. That and curiosity drive them. As poet Dennis Phillips told me recently, “What do you do when something really good or bad happens in your life? If you’re still writing, then that’s where you’re centered. Your art is your focus. Most people don’t make it big, but you can be respected. You keep exploring. You keep doing what you do.” I look for different ways to inspire my students. Recently, I showed parts of a documentary Joseph Campbell: The Hero’s Journey. Campbell studied and taught myths and mythic structure for years. He made a name for himself with the book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces. My favorite book of his is The Power of Myth, where Bill Moyers interviews him. I bring up Campbell because after studying myths from hundreds of cultures across time, he came to see many answers about living. Origin myths try to make sense of the world. Adventure myths have a certain structure, including having a mentor help guide the protagonist. One of Campbell’s big realizations about myths is that they instruct people who are now alive to “follow their bliss.” I don’t take this to mean, as many of our popular films and books show: “If you are persistent, you will succeed.” Rather, it says that your art centers you, gets you through the labyrinth of life. As Campbell says to Moyers, “The function of art is to reveal this radiance [transcendence] through the created object. When you see the beautiful organization of a fortunately composed work of art, you just say, ‘Aha!” Somehow it speaks to the order in your own life and leads to the realization of the very things that religions are concerned to render.” Your writing, your art, can lead you to what others might call spirituality. It’s your center. -- *For Vanessa Carlton’s great cover version of the Rolling Stone’s song “Paint It Black,” click here.  We live our lives to be conflict-free—yet whose life is conflict-free? How we deal with conflict shows who we are: monsters or milquetoasts, psychopaths or empaths. All told, people love conflict—not to be a part of it but to understand it. Look at when the freeway slows down. Sometimes it’s in your lane, but other times it’s on the other side of the freeway. Why does the clear side slow down to nearly a stop? It’s because people want to know what happened. Is anyone hurt? How did it happen? My wife and other people I know love the new cable television channel Investigation Discovery (ID), which I’ve dubbed “The Bludgeoning Shows.” The programming features real-life mysteries, most of them involving murder. These are horrible situations, and yet people want to know what makes an otherwise friendly and reasonable person kill? Is it for the insurance? For revenge? For love? What makes anyone want to kill? When it comes to writing a story, the engine of your story will be its conflict. It’s simple enough to create: invent a protagonist with a need or goal. Put up roadblocks to that goal, such as a person or thing that stands in the way. Then see what happens. Let’s say a young man looks for the right young woman. He finds her. What could stand in the way? His shyness or another suitor would work. Perhaps his family and her family hate each other. Shakespeare used that in Romeo and Juliet, as did Arthur Laurents in West Side Story and Stephenie Meyer in Twilight. Another way is that two people are polar opposites of each other, an odd couple, as in Beauty and the Beast, The Taming of the Shrew, and Pride and Prejudice. Ideally, your story has three or more major hurdles so that you have rising action. Offer surprises, and your readers may hang on. A study of J.A. Rowling’s Harry Potter series will tell you a lot. Supply Rich and Deep Conflict As simple as it sounds, writers often avoid conflict—perhaps because as people in the real world, we’re trained to stay out of danger. However, a huge fatal flaw in writing is when there isn’t enough conflict. I was reminded of this recently in my latest creative writing class as well as screening a friend’s first feature film, which he wrote and directed. Something inside many writers makes them avoid conflict or jump over it. Let me give an example. In my recent creative writing class, the writers had to turn in a final project of one long short story or two pieces of flash fiction. One of the most talented people in class wrote a sensitive story of two young men in the fifties finding they were attracted to each other. Instantly, one could imagine the conflict: distraught parents, homophobes who might beat them up, and ridicule in society. However, in this case, when one mother finds out, she’s okay with it but warns them. The two men become roommates, but no neighbor seems to notice their relationship. However, they worry, so they move out to the country, where they become huge fans of opera and are beloved by all the neighbors who never put together their relationship. (I also had to wonder which small town in California is big into opera?) Everyone is friendly, even if the two men remain wary of the larger society. In the end, they die as old men, only their dearest friends knowing about their relationship. Most people in our class discussion said they loved the characters, but something didn’t feel right. Most didn’t notice it was a lack of conflict. They felt the lack of conflict, though, even if they couldn’t point it out. A lack of conflict also created a lack of passion. Because these two men did not have to confront anyone, we did not witness what they could do for their love and beliefs. Deeper, Truer In life, most people believe they are brave and good, but what happens when a disaster strikes? Those fire fighters and police going into those burning buildings on 9-11 showed a lot. Another real-life disaster was in 1982, when an Air Florida flight crashed into the icy Potomac River in Washington D.C. Some people in the water called out for help. Some witnesses ran from the scene, freaked out, but one passenger who survived, Arland Williams, went back into the water to rescue others before he succumbed and died. Thus, conflict reveals character, and deep conflict reveals true character. One of your main jobs as a writer is to reveal character by showing how a person acts versus “telling” the reader about the person. “He was a brave person, very, very brave.” Do you think adding another “very” will make him braver? This is where “show don’t tell” comes into play. You reveal character by creating scenes of conflict, offering motivation, turns, and surprise. In upcoming scenes, you make things even worse. You are the god of your story, creating worse-and-worse conflict until we see your characters take charge, flee, or others succumb to too much pressure. Have Clear Conflict One of my former students started out his story well enough. His protagonist, a twenty-two-year-old young man living in Manhattan, wakes up late for work. Panicked, he dresses quickly, grabs a cold Pop Tart, which he eats on the way, and manages to flag down a taxi to get him to his job as a graphics designer. No one notices he’s late. He’s fine. Then he has a meeting to show off his latest ad, which he hasn’t finished. He makes bold decisions and draws like Da Vinci. Just as it looks like he’ll fail, his delivers and wows the clients. Then he needs to meet with his girlfriend at lunch. While she’s upset he couldn’t meet her parents, she loves him anyway. At this point, we don’t know what the story is about. He has a continuing series of little conflicts, but they add up to nothing. We don’t yet know his larger goal or what stands in his way. You, the writer, need to be clear what your protagonist needs. Get to it as quickly as possible. Don’t Jump Over Conflict One of the most common things I see in my students’ work is jumping over conflict. That is, they are often adept at setting up a situation, such two women fighting over the same young man. The women come to duke it out. One brings a knife, the other a gun. They show up at the right time in the park. Cut to them drinking together later, laughing, saying, “Why were we so obsessed with Johnny? You’re my friend, babe.” The other might say, “Yeah. We almost killed each other over something so stupid. I love ya, too.” We need to see the climax. Basic to traditional storytelling is that the protagonist and antagonist meet in the climax. Luke Skywalker meets Darth Vader. It doesn’t work to jump over the fight scene and flash to the next day with Hans Solo telling Luke, “Glad you did in Darth. The universe is better place for that.” Nor do we want to see Darth not show up in the climax. A nerdy little guy arriving who tells Luke, “Darth couldn’t make it, so I’m his cousin standing in” would not satisfy. Make the climax a climax. Avoid Passive Characters As simple as I’ve made the above sound, writing stories is hard, and I was reminded of this last week when my children’s literature students turned in their first short stories. It’s incredibly rare someone nails a good story on his or her first try, yet I always see potential in these first projects. An example is a woman who wrote about a clock named Pepe standing on a shelf of clocks in a hardware store. Our protagonist and goal become clear: Pepe wants to be bought. What does he do? Nothing. He simply watches as other clocks are bought, and he feels sad. That’s because he’s an inanimate object. He’s passive. Another of my students once had a similar problem with a ball of yarn who wanted to be bought. All the yarn did at first was yearn and do nothing about it. Once I suggested movement, the writer gave the yarn the ability to roll. After the yarn yearns, it rolls off the shelf right to the feet of the right older lady. Voila! Sale! From there, the yarn yearns to be used. The yarn finds a way, and we cheer for it. Scenes Need to Turn, and Conflict Helps This brings me to my friend’s feature film. I’ll call him Robert to keep his privacy. Robert has worked in the film industry for years on the production end, often as a second-unit director or cameraman. He wanted for years to direct a feature film about his grandfather, an Italian-American dry cleaner who became involved in the Mob. The two-minute trailer for the film makes it a must-see. I kept asking to see the whole film, so he showed me yesterday with some cast members. It’s shot well, acted well, edited perhaps as well as can be done, yet there’s not enough conflict. In part, that’s because many scenes do not turn. At the start, for instance, we witness an older man whose wife lovingly makes his lunch, and his adult son comes to help in the business. The scene is there to show how his family loves him. About ten minutes in, the wife accidentally bumps into a powerful mob boss’s car and damages his bumper. Instantly, we fear for them all, but the Don laughs it off, and our protagonist agrees to become the Don’s tailor—something he was hoping for anyway. The conflict quickly passes. My friend’s problem isn’t in the way it was shot or acted but in the script. Perhaps it can be re-edited for maximum conflict, but he may not have shot enough conflict. I mention this to show that even experts sometimes miss things. I repeat: creating a great story is hard. Humor Has Much Conflict I happen to have a funny streak, so when I focused on writing my novel Love at Absolute Zero, I first created a situation ripe for conflict. My protagonist, Gunnar Gunderson of Wisconsin, happens to be one of the world’s leading physicists. After his latest research project runs into a snag, he has three days free. He focuses on his own deepest yearning: to find a soul mate. Using the Scientific Method, he sets off to find his future wife. I throw all sorts of things in his way. While he may be a genius and a great professor, he’s also clueless in matters of the heart, including not understanding sex or love. He wears the wrong clothes, says the wrong things, misunderstands situations. I laughed to myself as I put on more pressure. At one point, he accidentally steps on the toes of a visiting Danish kindergarten teacher, falls for her as she does for him, and he moves to Denmark, a fish out of water, where things get progressively worse. You laugh at how bad it gets. In short, as a writer, you need to train yourself to revel in the conflict. You might create an outline for yourself and come up with possible conflicts. Perhaps you write out a dozen potential scenes where things are bad for your protagonist, and then use the best of them. Once you have those on your outline, imagine the situations getting even worse. I’ve had the luck over the years of having people from Pixar Animation speak to my now-former animation students, and the professionals explained something they did called “Plusing.” Once they created a scene, they would think of ways of making it even deeper, designing in more conflict and truths. Sometimes they’d spend hundreds of thousands of dollars to redo a scene. You have to be the god that tortures the people in your world—often to a good point. Comedy or drama, it’s conflict that engages your readers. Play with it. You’ll see.  In the zone. Been there? At times when I write, I may as well be sans body. I’m elsewhere. I could be a character on a gurney whose heart has stopped, and his spirit rises above the gurney, flows into the LED surgery lights above while he hears an echoey voice not unlike Sarah Jessica Parker’s saying, “Do you like black licorice?” “Yes,” I say. “Red Vines that are black.” “It’s time for the tunnel,” says the voice, “which is as black as black Red Vines.” My character, you see, is having an out-of-body experience—while I am. Writers, more often than not, tend to sail in their heads rather than on a real stormy sea. Hemingway? Okay, he was different. He liked boats and Buicks and running with the bulls. He’d say it was good. I’ve never found that good. Thus, I had to ask myself a few weeks ago why was I standing on the white edge of the Cornice at Mammoth Mountain in California, skis on my feet, contemplating the edge? I’d never skied the Cornice before, which required taking a gondola to the top, over 11,000 feet high. The snow was fast up there. Perhaps one shouldn’t stand on the edge of such a steep drop, with fast snow, especially on skis. The Cornice required some courage. Let me freeze frame me on that edge. The fact I still skied was nothing short of amazing. When my uncle took my cousins and me to Buck Hill outside of Minneapolis when I was twelve and threw me on skis, I was terrified. I hated heights. I hated being cold. I hated falling down. For the next sixteen years of skiing, I remained terrified. I stayed on the gentle slops and kept it up mainly because I liked the idea of skiing. I especially liked when the day was over and I’d survived. “It feels so good when I stop,” said a friend in high school, explaining why he was a long-distance runner. In my late twenties, on my yearly Lake Tahoe ski trip with my college roommate, Stew, I finally found a run I really loved, and I kept skiing it over and over in a fog that enveloped it that day. I could only see about fifteen feet in front of me. It was my kind of gentle slope. When the fog lifted, my eyes grew wide. My favorite run was actually long and steep. I realized then that my fear had been inside my head. “It’s in your head,” I reminded myself on the edge of the Cornice. I pushed off, curious to see what’d happen. Could I really make that first turn? My heart flew when I did. I created a kind of dance on the way down, not falling but quickly turning, quickly observing, quickly avoiding ice and heavy bunches of snow. I’m explaining this as a way to also explain how writing stories is for me. I might have a great idea for a story, but I don’t know where it’ll go, or what it’s about, or even why I want to write it. I push off into it to see what happens. Skiing is of the moment. Sometimes things work smoothly, but there are always surprises—ice, rocks, turns that throw me off. Similarly, writing always surprises me. Characters say and do things I didn’t expect, and such moments can change my plans. I might zip off on a tangent and have to get back. Like author Kurt Vonnegut, I often think I can’t do this again—either write or ski—but I try anyway as with this very piece. All I knew for this was I wanted to write about the mind/body experience. For my last novel, A Death in Vegas,all I knew was that my protagonist had his own company that sold beneficial bugs for organic gardening—ladybugs and the like. I knew he found a dead woman in his hotel room on the morning of a Las Vegas convention. He had nothing to do with it. The Las Vegas police suspected him. Wwhich ho set him up? Once I started writing the story, I paused to outline, following paths, adjusting, trying new things. That’s because I can think faster than I write, and brief notes in an outline lets me zoom quickly. Six drafts later, after I honed, adjusted, tried new things, I was done. My characters and story had grabbed me. I’m not prone to exercise. I have to push myself. I swim because it gives me energy to write. Skiing takes me away from writing—yet I always return refreshed and energized. To write well requires being physical. I have to put my body into the world. The skiing at Mammoth beyond the Cornice on my recent trip often made my thighs scream. The snow was heavy. I fell twice, not having fallen once in my previous nine days of skiing this season. Yet I amazed myself that I could do this. Skiing requires precision. It requires stamina. It requires a belief that your body will know the way. Philosophers often focus on three elements: mind, body, and spirit. If you push off into the white page as well as onto a white slope, that third element, spirit, seems to soar. You find yourself in the zone. I love the zone. -- I originally wrote this for Free Kindle Books and Tips, which you can see by clicking here.  "Out of Denmark" l-r: Fruelund, Semmel, Aiken, Leine "Out of Denmark" l-r: Fruelund, Semmel, Aiken, Leine With around 530 panels at the AWP writers conference, recently concluded last weekend in Minneapolis, it’s not difficult to find sessions that mirror one's interests. For instance, I’m writing a novel based in the Iraq War. Not only did I find one that explored war, I found seven and made it to four. However, was I willing to explore areas that didn’t presently touch my life? Perhaps the most esoteric panel I attended was “Out of Denmark: Danish Novelists and Their Work.” Beyond Isak Dinesen’s Out of Africa and Peter Hoeg’s Smilla’s Sense of Snow, I didn’t know much about Danish literature other than an awareness that Danish detective fiction had a good following. In fact, last year I’d picked up a copy of Copenhagen Noir edited by Bo Tao Michaelis, but hadn’t read it yet. Knowing I’d be travelling to Denmark this summer, I sought out this panel and was rewarded. The panel featured two Danish novelists, Simon Fruelund and Kim Leine, and two translators, Martin Aitken and Kyle Semmel. As moderator, Semmel explained how Denmark is a small country, and its writers are a small community, even if some of them work in obscurity until they make it internationally. When Aitken translated Dorthe Nors’ Karate Chop, she wasn’t known—and then the story collection brought her recognition first internationally and then back home. Even though there were only two writers on the panel, I came away with a sense of the breadth of contemporary Danish fiction. Leine, for instance, won the Nordic Council Literature Prize for The Prophets of Eternal Fjord, an epic tale about a newly ordained Danish priest, Morten Falck, who travels to Greenland in 1787 to convert the Inuit to Lutheranism. There’s a collision between the Greenlandic and the Danish cultures. It will be published in translation in the U.S. in July. To get a sense of the sound and rhythm of his work, Leine read short passages in Danish, then his translator, Martin Aitken, read the same passage in English. Aiken said he translates with music in mind. He tries to capture the poetry of the book. In Leine’s voice, the sense of older Danish had to be carried over in English. “The main thing was the feel of the piece,” Aiken said. While I had my doubts about a story set in 1787 Greenland, they quickly vanished when Aitken read, offering a life-and-death situation set on a high cliff above the water. It reminded me how I fell into James Clavell’s Shogun, which was 17th-century Japan. Fruelund read in English from his newest book, Civil Twilight. It’s probably at the other end of the spectrum from Leine’s novel. Rather than traditional storytelling on an epic scale, this novella offers vignettes of people living on a single street near Copenhagen in the 21st century, and the snapshots of these people build on each other to reveal, as translator Semmel says, “that sections interlock, like pieces in a jigsaw puzzle.” As Semmel states in the foreword to the book, “You will not find a single word to clog the gears. He takes great care with his language, crafting it with precision, and his creations are the literary equivalent of Danish Design: smooth, clean, “minimalist” constructs that are built to last.” Fruelund said Carver and Hemingway had influenced him, and that to be a Danish writer, he had to consider “provincial vs. international. The Danish writer has to have this in mind.” In all, I left even more curious about Danish writing and will read more. This idea of pushing your sense of curiosity, by the way, is mirrored by film producer Brian Grazer, whose new book A Curious Mind: The Secret to a Bigger Life, explores how to keep open to new things. He says part of the challenge is you’re in a situation where people are superior to you in a certain area, and you have to be comfortable with that. In college, students accept it naturally, but older adults often don’t like to feel inferior. You have to get over that. Says Grazer, “Curiosity has never let me down—just the opposite. The only questions I regret are the ones not asked.” You can read the Los Angeles Times’ story on him by clicking here.  It snowed briefly over two days at the AWP Conference. Most members were inside at panels. It snowed briefly over two days at the AWP Conference. Most members were inside at panels. Now that I’m back in Los Angeles from Minneapolis, I can consider more of what I’d taken in. Among over 180 panels offered at the AWP Writers Conference on the first day, I managed to make it to four. Three had to do with trauma and war. It’s not coincidental. I’m writing a novel based in the Iraq War, 2007. On another day, I made it to another panel on war writing, missing two others. What amazes me is that the subject is popular. Then again, we live with war all the time. It’s bound to affect writers. The first panel, “Mining the Gap: Trauma, Memory, and Reimagined Pasts,” featured five authors, Elizabeth Kadetsky, Elyssa East, Jessica Handler, Denise Grollmus, and Rebecca McClanahan, discussing how trauma changes human beings. As the conference schedule described it, “Grief, trauma, and nostalgia can reshape our memories, erasing fragments or creating insistent, nonlinear repetitions.” Not only were the authors all women, but so was most of the audience of a few hundred. When a panelist pointed that out, everyone looked around, and many eyes fell on me as if, What made this guy come? My smile said, Isn’t trauma gender neutral? As Kadetsky then ventured, “Women tend to talk about their feelings more. Women traditionally are the nurturers.” Perhaps so. When I taught “Vietnam Through Literature” at CalArts in the 90’s, the course filled quickly. Many of the students’ fathers had served in Vietnam, and the fathers had never talked about the war. These students wanted to know about their dads at war. Later at AWP, I learned that one-in-three women in the armed services are sexually assaulted. (I found a VA study confirming this.) That could be another reason why more women than men were there. As I learned elsewhere later that day, VA hospitals have a whole unit devoted to women—and men—who have been sexually assaulted while defending their country. The second panel I attended, appropriately, was “Women Writing War,” with Emily Tedrowe, Jehanne Dubrow, Katey Schultz, and Andria Williams. This panel considered the feminine imagination vs. male imagination. One way they did that was read from their work and let the work speak for itself. I fell into their stories, admiring how they pulled me into the moment. One of Katey Shultz’s short stories from Flashes of War, flash fiction based in Afghanistan during war, featured a scene where “bullets rained like a Carolina downpour.” Many of her comparisons grabbed me. Here, as later with the other panels, writers also had to confront “credentials and authority.” Did one have to experience war to write about war? Andria Williams, author of the upcoming novel The Longest Night from Random House, has been a military spouse, and writes vividly from that point of view. Katey Schultz is not a veteran, yet her stories dive into Afghanistan and often into battle. She did so through meticulous research and, as she says, “through observation, empathy, and imagination. The truth is driven by emotion and not fact. I try to avoid stereotype whenever possible.” As poet and memoirist Brian Turner said in the next panel, “Writing in Response to War,” “It’s easy to capture facts. It’s harder to get to the truth.” In this third panel, Turner, an Iraq War vet, joined poet and Vietnam vet John Balaban to go over certain truths. As Turner said, “I was scared shitless most of the time there.” Most of the time nothing happened, punctuated with moments or minutes of shooting and explosions. His collection of poetry, Here, Bullet, opens with this short piece: The word for love, habib, is written from right to left, starting where we would end it and ending where we might begin Where we would end a war another might take as a beginning, or as an echo of history, recited again. They each read from their published work. Turner read from My Life as a Foreign Country, and one could grasp how his poet’s soul used prose to best advantage. The moment a U.S. Army boot hits the door of an Iraqi house so the soldiers could question the family inside for information, one feels for the members of the family as well as the naïve young men of the Army, trying to be friendly in their high-tech gear. A student at Harvard at the start of the Vietnam War, John Balaban read from his memoir, Remembering Heaven’s Face: A Story of Rescue in Wartime Vietnam. He had voluntarily enlisted, but as a conscientious objector, having grown up Quaker. He often worked in hospitals in Vietnam, sometimes overseeing burned and injured children from the war. As Turner and Balaban each read vivid passages, I couldn’t help but think that war betrayed how utterly cruel people can be. A tsunami of horror sweeps over soldiers and citizens. How can one possibly absorb it? PTSD is as common as eggs. As Balaban read a passage about a child on an operating table and how deeply injured the boy was, I squirmed. His voice cracked, and he was near tears. This is after perhaps forty-five years from the event, and it still chokes him up. Balaban said his goal was, “I want you to know the worst and still find good.” This is exactly where I’m at in my novel, seeking a sense of contradiction as I’m working with my friend and Iraq war veteran Samuel Gonzalez, Jr, who was in the military police in Iraq. Half of his platoon were women. They were fighting on the front line. A woman was often Gonzalez's gunner. The notion that women aren’t fighting is wrong, and I’m most curious about the mixing of men and women soldiers during combat. Is it different than an all-male Army? Might my protagonist fall in love in war? On Saturday, I attended, “Telling Our New War Stories,” again with Turner and Schultz, joined by Benjamin Busch, Phil Klay, and Siobhan Fallon. Turner spoke of the difficulty of trying to understand what he experienced. He felt that a war novel shouldn’t end crisply with understanding but with a sense of layers of meaning and confusion. “We can learn things when we get to a dead end.” Siobhan Fallon writes short fiction to understand things. For her collection You Know When the Men are Gone, she related how she and her husband, living in Ft. Benning, Georgia, were giving a cocktail party when the neighbors next door began to argue loudly. “It’s a good image for military life,” she said, “in housing projects with thin walls.” Phil Klay, too, writes fiction. He was writing a novel and short stories at the same time and discovered that, “The stories allowed me to go in at different angles. I wanted a bunch of voices who didn’t necessarily agree with each other." He abandoned the novel and created the collection Redeployment, which takes place in both Iraq and Afghanistan. Turner said while in Iraq, he was writing diaries, then later, poems. As he said, “Why share them? War is part of our culture. The word ‘complicity’ is one of my driving words, something difficult to live with. Maybe that’s some small way to be a part of the conversation.” Klay added, “When I came back from Iraq, I was asking what the hell was that?” People back home seemed to talk about the war in a way that was so odd, he said. “Something was missing. What was it? I tried to figure it out. I didn’t have the notion of writing a work of art. It was about writing to say something. It’s a letter to you. You should respond.” Moderator Benjamin Busch, author of the memoir Dust to Dust, ended in saying in writing about war, we have to avoid the expected tropes. “It seems people want to see the worst shit, but there were fun times, funny times, too—and beauty.” There has to be more beyond the battles—perhaps the healing.  The "Publishing Sucks" panel - AWP Conference 2015 The "Publishing Sucks" panel - AWP Conference 2015 “Publishing sucks—even when you’re good at it,” read the blurb for this panel at #AWP15, the writing conference I’m attending in Minneapolis. Every writer and artist I know drags around the dead reedy bird of rejection. It’s when we feel unworthy. We devote our lives to an art and craft, and sometimes we wonder if it’s worth it. Thus, this panel was held in one of the larger halls, and still people had to sit on the steep carpeted stairs to fit in. I pictured each person ready to grab a torn battle flag fallen to the ground and jam it proudly aloft. We’re still alive. As the moderator, Jill McDonough, said, she couldn’t help feel a shadow cross her heart when she passed the Paris Review booth at AWP. “Curse you, Paris Review! You could have published me,” I could imagine her yelling. How many of us could warm ourselves through a winter burning rejection slips? None of us return the favor, though. “I’m sorry, Tin House. Your journal doesn’t meet my needs at this time.” I’ve been on the other side, however, as the senior editor at a small publishing house, the late Prelude Press. We published computer books, yet we received manuscripts for novels, self-help books, and children’s picture books, among others. We did not seek such things. Still, the heavy entries came, often with a poorly written cover letter such as, “This here picture book my nephews loved. It will make you lots of munny. How much munny will you give me now?” At Prelude, the worst and funniest query letters went on the employee refrigerator. We’d grab our bag lunch and laugh. Ever since, my goal has been not to end up on any publisher’s refrigerator. The panelists for this event included poets Kimberly Johnson, Major Jackson, Jay Hopler, and novelist Brando Skyhorse. They each had their war stories, such as Hopler once interned in college for a major journal, and his job was simply to put the rejection slips in the 10,000 submissions that needed attending to. He was told not to read any of the poems because there weren’t enough hours in the day. “Just make sure you don’t include their cover letters back. They really hate that,” he was told. Thus, it was an exercise in mailing. (Didn’t you ever wonder if some places did that? Zyzyva seemed to send me a rejection faster than I could return from the post office.) Rather than dwell on how tough and difficult publishing is, the panelists offered practical things people could do. One of the major themes was, “There’s no replacement for a really good editor.” If you’re serious about a manuscript, hire an editor to help you before sending it anywhere. I’ve found that true. While I’m a strong editor, I can’t be objective about my own work. I hire an editor. Major Jackson, poetry editor for The Harvard Review, mentioned he hated cover letters that oversold the writer by listing publications. He could care less how much you’ve been published. He wants a short letter. If you mention a poem you liked from a previous edition, that would tell him more than your publications. He also felt that “most of publishing is luck. The joy should be in the writing.” He later added, “Seventy-five percent of what you do should be the writing. The rest is building an audience.” Brando Skyhorse said he’d been in the UC Irvine writing program with Alice Seybold and Aimee Bender, two writers who became quite successful after graduating. In fact of the seven in his class, six got published quickly—everyone but him. It took him thirteen years. In the meantime, he worked as an editor for a large publisher, and had to reject people. The work sharpened his sense of quality, helpful now as a writer. It occurred to me that while many writers aim for and seek a large publisher, when they get frustrated, they decide to do it themselves and self-publish. While it’s a valid choice, there’s a middle ground—the small publisher. A hundred yards from where the panel was held, the AWP annual Bookfair buzzed with attendees. Among the nearly 800 booths and tables stood an array of small publishers willing to talk with anyone. Many featured their head editor. I talked to many this time knowing I’d be writing this. I discovered something I never knew. Most small publishers make little to no money. Some are non-profit companies. They all do it for the love of discovering great new work. They take pride in the quality of their publications. While a small publisher will never have the marketing muscle of a larger one, plenty of authors get little to no marketing help with a large publisher. Large or small, you get the cachet of being published. As I wrote in yesterday’s post about real writers and publishers, you’ll have to do much of the marketing yourself anyway. If you click here, you can get the list of exhibitors from this year’s Bookfair. You can look up their submission policy online. Consider coming to next year’s AWP conference in Los Angeles. Perhaps you’ll have finished your new manuscript by then. Any writer can join the AWP. It can be lonely as a writer, yet when you are among many others, you feel a sense of community. When you hear someone really great at a reading as I did yesterday with Susan Straight, Ron Carlson, and T.C. Boyle, you are energized. Brando Skyhorse ended the discussion with, “Publishing sucks, but writing doesn’t. Good work always finds a way…eventually. How long are you willing to wait for eventually?” I’ll add, what are you willing to do differently to get published? Hire an editor? Write another book? If you have suggestions or your own publishing war stories, feel free to add a comment. |

AuthorBefore I wrote novels and plays, I was a journalist and reviewer (plays and books). I blogged on Red Room for five years before moving here. CategoriesArchives

July 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed