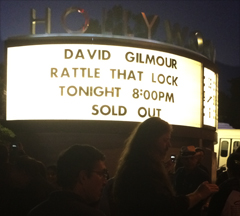

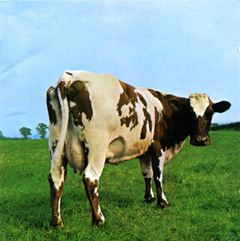

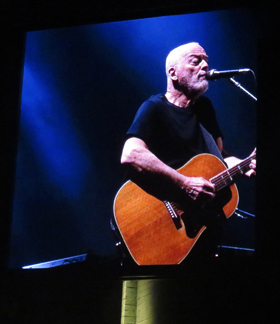

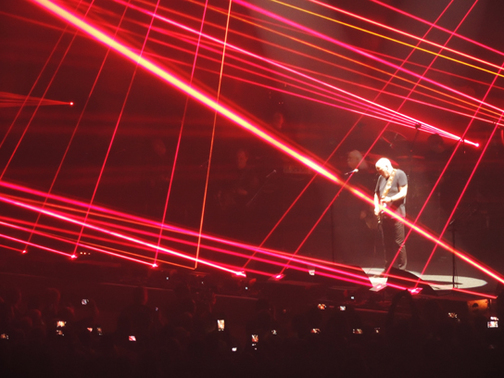

I’ve been going to rock concerts more steadily over the last few years. It’s something I did in high school, yet now that I’m older, I ask myself why now? It’s a rediscovery of the mystery of music. I’m not clear how great music works, or how people make it, yet I sense it’s similar to why I write fiction. For me, writing does several things. By slamming different characters and situations together, I witness people struggle, trying to attain whatever their goals are, much as I am. Sometimes, like me, they are also trying to understand things. Yet there’s also the mystery I love in writing. I’m never sure if a story will work out—and sometimes it doesn’t—but I’m curious to see what will grow. As author Rick Moody wrote after his novel The Ice Storm, “Sometimes I think words are so beautiful so flexible so strange so lovely that they make me want to weep, for the import, for their proximity to eternal mysteries.” Maybe it’s also why I cultivate tomatoes and flowers. A little plant or seed becomes a big thing, and I don’t get how, but it’s amazing. Same in music. So let me try to unravel David Gilmour a bit.  First, progressive rock has been on my mind this week with the passing of Keith Emerson of Emerson, Lake, and Palmer, and now with my experiencing David Gilmour of Pink Floyd fame for two nights at the Hollywood Bowl. As British musician Arthur Brown noted, progressive rock originated in the United Kingdom “as an attempt to give greater artistic weight and credibility to rock music.” It includes such bands as Jethro Tull (my first concert ever), Yes, ELP, and, of course, Pink Floyd. Progressive rock pulses in its own niche, a sound much different than Bruce Springsteen, for instance, whom I wrote about last week. Springsteen delivers short narratives and comments on life, while Gilmour’s songs often have a hypnotic rhythm, searing solos, and ponderous lyrics. With Springsteen, you might experience being down-and-out in a city, yet finding passion or hope to deliver a new destiny. With Gilmour and Pink Floyd, you become what philosopher Martin Heidegger might have hoped for you: present in the moment. Thoughts of your daily life and even your body seem to disappear into feeling the sights and sounds before you. I discovered Pink Floyd in high school in Minnesota. A classmate and musician brought in the group’s fifth album, Atom Heart Mother, and loaned it to me. This was music unlike anything I’d heard—not the standard three-minute singles on the radio. The first side of the LP sailed along as one song, six parts, for over 23 minutes. The other side included “Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast,” a 13-minute piece that mixed people eating breakfast and playing music. On the same side, I loved “Fat Old Sun,” whose lyrics gently looked at a summer in the country with the sun setting, written by Gilmour. The cover of the album had a cow on green grass turning its head to the viewer. The band’s name appeared nowhere on the cover, and you could not find pictures of the band. In fact, I can’t recall ever seeing members of the band on any Pink Floyd album, so I came to think of Pink Floyd as just a thing, a unit.  When I became a senior in high school, my school offered for its first time a chance at independent study, so I made one in filmmaking. I created a Super 8 film that simply rattled off still images—often just four frames at a time—of things that influenced my life at the moment, in sync with Pink Floyd’s song, “One of These Days,” which ran 5 minutes, 57 seconds. The song came from the Meddle album, which I blasted though my quadraphonic sound system. My movie influenced my becoming a film major in college. Later, my love of imagery and sound led me to writing. When I arrived at the University of Denver in 1972, I learned Pink Floyd would play at the school’s arena that week—a good sign. I walked over with my cousin Peter, who attended DU at the same time. (This being 2016, the Internet has the set list from the concert by clicking here.) The band played much of its upcoming album Dark Side of the Moon, which when released in 1973 would become an immediate hit, topping the Billboard charts for a mind-boggling 741 weeks (over fourteen years). Clearly, the album tapped into some of the eternal mysteries of life. My memory of the concert wasn’t about any of the band members, but the use of fog, incredible lighting with colors that changed in a flash, and extended songs that made me float along with words that somehow sounded reassuring. In 2006, my friend Riff Root said he went to David Gilmour’s amazing concert in Hollywood. Root had been the ombudsman at DU, and was now an entertainment attorney in Santa Monica. “Gilmour? Who’s he?” I asked. “You know, the amazing guitarist from Pink Floyd.” As much as I’d liked the band, oddly I never learned who was in it. I did after that. I learned how each member contributed masterfully, too: Gilmour with his guitar and lead vocals, Nick Mason on drums, Roger Waters, who wrote many of the lyrics and played bass, and Richard Wright, the genius at the piano and keyboards. Syd Barrett started with the band but creeping mental illness had him drop out in 1968, and 1975’s album Wish You Were Here was a tribute to him. He died in 2006 of pancreatic cancer. After hearing Riff go on and on about the Gilmour concert in 2006, I vowed if Gilmour ever came back, I would go. It took ten years. My desire was reinforced when I watched the DVD of Gilmour’s concert at the Royal Albert Hall, Remember That Night. (You can see the songs “Breathe” and “Time” from that concert by clicking here. It features Richard Wright on keyboards; he died in 2008 of lung cancer.) I went to buy tickets for the Gilmour concert at the Hollywood Bowl a half hour after tickets went on sale. My high school friend Jim said he’d go with me as my wife didn’t like the band—too “out there.” The concert was already sold out. A second concert was added, and I grabbed tickets. When my cousin John wrote weeks later that he’d fly from Idaho to see Gilmour, I bought a pair on resale for the first concert. Thus, I’d go two nights. That first night, I had high expectations for the concert. John and I found our seats in Section D, right near the center boxes. The lights went out, and fog started filling the stage under a blue light. I became tense with anticipation. Gilmour and his eight-piece band launched into his new album, Rattle That Lock, playing the title track. The performers moved as mere silhouettes in the heavy fog and blue and purple backlighting.  A giant disk that hung from the Bowl’s band shell came to life. The disk had three uses during the night: as a canvas to beam out changing colors, a video screen to show closeups of Gilmour and band members as they performed, and as a screen to show animated and filmed clips to reinforce the music. The disk also featured computer-controlled lights on its outer edge. The first hour brought a combination of Gilmour’s solo work, and the Pink Floyd songs “Wish You Were Here,” “Money,” “Us and Them,” and “High Hopes.” The last featured the Division Bell from the album of the same name. After a short break, Gilmour began with “Astronomy Domine,” a song from Pink Floyd’s first album before Gilmour had joined the group—flowy, eerie stuff, the very thing that loses my wife but I adore. After a brief intermission, the second set brought “Shine on You Crazy Diamond,” “Fat Old Sun,” and seven other tracks. The first evening also included David Crosby of Crosby, Stills and Nash, who joined Gilmour to sing four songs—an extra treat. In many of the evening’s songs, Gilmour could zip into moving guitar solos, often in the high range of notes, yet I never felt he was showing off or proving himself. Still, at age 70, he’s forceful. His solos also never felt as if he were noodling for purpose like a jazz musician trying to find the main thread. Rather, he gave a sense of driving ahead, sure of himself, making each moment count—mesmerizing, bending the strings, pushing his tremolo bar, arcing for the exact notes he needed.  Gilmour ended the second set with “Run Like Hell” from The Wall. The song starts at a fast pace. I sometimes listen to “Run Like Hell” on the treadmill when I exercise. It forces me into an exact 4 m.p.h. fast walk. (I’ve hit the time of life where I need to consciously exercise to keep in shape before I reach that great gig in the sky.) At the concert, “Run Like Hell” offered a frenetic pace of different-colored lights clicking down on Gilmour while the other members played in the dark. The stage lights grew brighter and ever-changing, and each player wore sunglasses. The instrumentation escalated while a chorus sang “Run, Run,” and it all ended in a warfare of fireworks, timed to the fast pace and growing into so many rockets that the Hollywood sky became bright white, as did the stage. How could he top that? Gilmour merely said, “Good-night. Hope to see you again.” He and the band strode off. Of course, no modern concert can merely end like that. In the old days, people would hold lighters aloft while others clapped hard. Now we display lit-up cellphones. The group returned with an encore of “Time” and “Comfortably Numb,” with the disk and the band shell pouring out clock images; the last song offered an array of new lighting effects including reflected lasers that framed Gilmour and shot above the audience. Crosby sang the words to “Comfortably Numb” that first night. The second night was much the same, other than “What Do You Want from Me?” replaced “On an Island” from the first night. The second night let me absorb more, see more, and watch how tightly formed each piece actually is. I felt as satisfied as on the first. It was also fun seeing Jim behold Gilmour live for his first time. He, my cousin John, and I witnessed a portion of rock history. Gilmour, too, reminded me to keep pushing and exploring. As he sings in “Time,” “The sun is the same in a relative way, but you’re older / shorter of breath and one day closer to death.” The concert had to end with “Comfortably Numb” for two reasons. It’s one of a few songs the audience actually knows the words to and sang along. It also offers the line, “There is no pain. You are receding / A distant ship, smoke on the horizon.” Perhaps it’s a comfortable way to think of the end.

1 Comment

3/28/2016 06:14:53 pm

Phenomenal performance. Recommended to the highest. Only improved upon by the face time with my cousin Chris Meeks. Beautifully written Chris. Even more, beautifully lived.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorBefore I wrote novels and plays, I was a journalist and reviewer (plays and books). I blogged on Red Room for five years before moving here. CategoriesArchives

July 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed