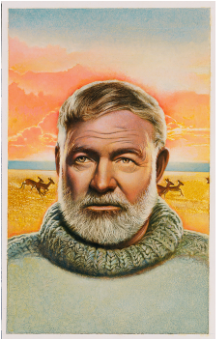

Ernest Hemingway Ernest Hemingway When I took my first creative writing class, a poetry class, in college at the University of Denver, I did it because I needed to fill in some credit hours. English had never topped my hit parade because most of my professors had made me feel that to truly understand a book, you needed to be an English major. I was not. I was into psychology. Little did I know then that psychology would be important in reading and writing. My last required English class, one in American Literature, turned me around. I couldn’t believe that in Ernest Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, the protagonist, Jake Barnes, was impotent—although I didn’t know that word then. I surmised, though, that his penis somehow didn’t work right, and could we really be reading about this in a class? Was it legal for a writer to write about that? How were we going to talk about it? I learned that Hemingway had traveled to Spain in 1925, and a lot of those experiences such as the running of the bulls had ended up in his book. He’d had a few wives, so apparently impotence wasn’t a problem. Maybe it was when he killed himself on July 2, 1961. After that, I also discovered that an F. Scott Fitzgerald story that we read, “The Rough Crossing,” was based on a trip that Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda had taken. I hadn’t known until then that it wasn’t cheating for writers to draw from their lives so directly. Also in “The Rough Crossing,” I was impressed how the storm at sea matched the storm in the characters’ marriage. That was a clever thing. When I took the poetry writing class, I drew from my life, as did many of the other writers in the class, and it was fun. Symbols emerged in some of the poems, which could add extra meaning. I learned of other poetic devices, such as alliteration and onomatopoeia. This word stuff was amazing. Another important event in my life was that I spent part of my junior year abroad in Denmark. I learned about language in a whole new way: if you don’t know a language, it’s difficult to communicate. In high school, I’d taken Spanish and Latin, but because Minnesota didn’t have many people speaking either language, I never felt any urgency to learn. In Denmark, I really wanted to understand what people were saying around me. I took Danish, and I came to see that understanding another language also gives you clues to how a large group of people think. After all, language guides our thinking. Danes have some dozen words for “snow,” yet they have the same word for “fun” and “funny,” which to us are two different concepts. There, I also spent a lot of time reading English-language novels that I picked up in a local library because I had a lot of time to myself. I’d never been much of a reader until that point. Books were incredible. How had I missed that before? I’d discovered Kurt Vonnegut’s books in Denmark, and while the story lines were wild and of science fiction, much truth rang out to me. In Cat’s Cradle, for instance, Vonnegut created words for things that had no previous words. A “karass” is group of people linked in a cosmically significant manner, such as those in a Corvette-owners club. A “duprass” is a karass of two: two people who are so deeply connected, they are their own universe. They often die within a week of each other. I read voraciously abroad. I remember looking for the thickest book in English at the Danish library. It was Of Human Bondage by Somerset Maugham. I read it on buses, trains, everywhere. Wow. After college and a few years of jobs selling things such as men’s clothes, cameras, and ceramic tile, I went on to earn an MFA in creative writing. In 1994, I started teaching creative writing at CalArts after I’d been publishing a lot of articles and reviews and writing short stories and plays. One thing most creative writing classes don’t have time for is reading published stories and books. Nonetheless, I would slip in a few. Why reinvent the wheel when writers before us have done some amazing things? Reading great stories gives you permission to experiment. In my third year of teaching, the chair of the English department at Santa Monica College called me out of the blue, having heard I was an inspirational instructor, and she asked had I considered teaching English? I hadn’t, but I took up her offer. My challenge was, “How do I stir my future students in English a way that most of my English professors had not?” The main thing that had turned me off was in reading older books about older characters that I had no connection to. I thought I’d use contemporary nonfiction narratives and novels, trying new things every semester, one by a female author, one by a male, to keep me on my toes. It has worked. I assign the reading and a few questions to go with it, and my students and I sit in a giant circle and discuss it, like a book club. Everyone talks. I also instruct them how to read more actively. Reading with a pen in hand helps. They should underline or highlight things that speak to them. If they have a question about something, write it in the margin. The first time a major character is introduced, put a bracket around it. For example, J.K. Rowling in the first Harry Potter book introduces Hagrid with “hands the size of trashcan lids” and feet “like baby dolphins.” When you write in your book, you interact with it. You make it your own. If it’s your book, you can write in it. I delight when students—and it happens often—say something like, “I’ve never been a reader, and I didn’t think I’d like reading this, but I couldn’t put it down.” One student told me, “It’s weird. It’s like a movie in my mind. I’m looking at ink on a page, and suddenly I’m in these people’s lives. I love it.” I’ve used such books as Patti Smith’s Just Kids, about her years after high school in New York, and she and Robert Mapplethorpe struggled to find what to do with their lives. Novels such as In the Lake of the Woods by Tim O’Brien and Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake worked well. Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five had only a lukewarm response, but his Cat’s Cradle found converts. I’ve ended up creating a list on Amazon’s Listmania of the most successful books I’ve used, which you can see by clicking here. These are books that engaged nonreaders, and you may enjoy them too. Many of my students are surprised they like reading and want to know how to find more books. With perhaps two million books published each year, there absolutely are new things you will love. You just have to find them. Services such as BookBub, BookGorilla, and BookSends help you discover new books at bargain prices. They send you a handful of links to highly rated books each day whose eBooks are on sale. Choose the category of books you like, and in this daily email, you are likely to find things that grab you. I know I’ve ignited a number of students into reading. Reading helps a person think, feel, and see the world in fresh ways. It may inspire you to write, and writing draws you into thinking and understanding more deeply. May you find the frenzy of reading. Reading is life.

4 Comments

2/18/2015 07:21:51 am

I wondered that too about Jake Barnes and felt that I grew up with SAR, reading it and Gatsby in college, then every summer after that, always around the longest day of the year-- as I aged, Jake and Brett Ashley and even the Count transformed, an exercise difficult to assign in class but easy to assign in life.

Reply

Michael Rasmussen

2/24/2015 04:39:36 am

Nice whirl around reading inspiration.

Reply

MichaelRpdx

2/24/2015 04:40:59 am

Google is still a friend:

Reply

2/25/2015 02:25:45 am

Thanks, Michael, for telling me the link didn't work. Now it's fixed. Best to you, too, Millicent.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorBefore I wrote novels and plays, I was a journalist and reviewer (plays and books). I blogged on Red Room for five years before moving here. CategoriesArchives

July 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed